Theories and Methods

PHIL 210: World Religions

Chapter 1, Day 3: Theories, Methods & Application

How do we study religion academically?

Academic study of religion uses multiple methods and theoretical frameworks.

⌨️ Keyboard Shortcuts

→ / Space: Next slide

← : Previous slide

S: Speaker notes

F: Fullscreen

O: Overview

ESC: Exit/Close

Functionalist vs. Substantive Approaches

Functionalist Approach

Question: "What does religion DO?"

Focus: Social, psychological, economic functions

Thinkers: Marx, Freud, Durkheim

Substantive Approach

Question: "What does religion MEAN?"

Focus: Ideas, experiences, intentions

Thinkers: Otto, Eliade, Tylor, Frazer

Neither is more "correct"—they ask different questions and reveal different aspects.

A theoretical approach that explains religion by examining what it DOES rather than what it IS. Asks: What functions does religion serve?

- Social cohesion (Durkheim)

- Psychological comfort (Freud)

- Economic control (Marx)

- Legitimating authority

Can be reductive if it ignores what practitioners consciously believe/intend.

A theoretical approach that explains religion by examining the IDEAS and EXPERIENCES that motivate people. Asks: What do practitioners believe/experience/intend?

Focus on: religious ideas/doctrines, phenomenology of experience, meaning-making, conscious motivations.

Can miss unconscious social functions if it only looks at explicit meanings.

What Does Religion DO?

Functionalists ask:

- How does religion create social cohesion?

- How does religion provide psychological comfort?

- How does religion legitimate authority structures?

Key Functionalist Thinkers:

Karl Marx (Economics): Religion numbs people to exploitation

Sigmund Freud (Psychology): Religion meets need for father figure

Émile Durkheim (Sociology): Religion reinforces group identity

Max Weber (Sociology): Religion influences economic systems

Note: Functionalism doesn't necessarily dismiss religion—it analyzes what religion does rather than whether beliefs are true.

What Does Religion MEAN?

Substantive theorists emphasize:

- Conscious human intention, emotion, and agency

- What practitioners think they're doing and why

- The content of religious ideas and experiences

- Irreducibility of religious meanings (can't be "explained away")

Key Substantive Thinkers:

Edward Tylor & James Frazer (19th c.): Religion as explanation of phenomena

Rudolf Otto: Religion emerges from numinous experience

Mircea Eliade: Religion cannot be reduced to social/psychological factors

Same Practice, Different Questions

Example: A person fasts during Ramadan.

Functionalist Questions:

◆ Does this create group solidarity?

◆ Does fasting build self-discipline?

◆ How does it reinforce religious authority?

◆ Does communal fasting create social bonds?

Substantive Questions:

◆ What does the person believe about Allah's command?

◆ How do they experience their relationship to God?

◆ What theological meanings does fasting carry?

◆ What spiritual transformation do they seek?

Both are valid questions about different aspects of the same practice.

The ninth month of the Islamic lunar calendar. Muslims fast from dawn to sunset (no food, drink, smoking, sexual relations). One of the Five Pillars of Islam.

Commemorates the first revelation of the Qur'an to Muhammad. Emphasizes self-discipline, empathy for the poor, spiritual reflection, and community solidarity.

Early Substantive Theorists

Edward Tylor (1832-1917) & James Frazer (1854-1941)

Why they're here (and why this is NOT the last word):

We place them under substantive because they offered content-based accounts of what religion IS—even though their evolutionary assumptions are now widely rejected.

Their Arguments:

- Religious belief originated as explanations of natural phenomena

- Beliefs in spirits attempt to explain life and death

- Religion evolved from "primitive" forms to monotheism, then to science

Frazer's influential 13-volume work on magic and religion (1890-1915).

British anthropologist, pioneer in cultural evolution theory. Coined term "animism" to describe belief in spiritual beings. Argued religion evolved from simple to complex forms.

Major work: Primitive Culture (1871). Used term "primitive" to describe "earlier stages"—now rejected as ethnocentric and colonialist.

Scottish anthropologist and folklorist. Compiled massive cross-cultural study of myth, magic, and ritual.

Major work: The Golden Bough (13 volumes, 1890-1915). Influenced by evolutionary assumptions now considered problematic.

⚠️ Critical Context: Why We Study Them

⚠️ Tylor and Frazer used the term "primitive"—reflecting 19th-century colonial assumptions.

Their evolutionary model is now widely rejected because it:

- Wrongly assumed European Christianity was the "highest" form

- Wrongly assumed indigenous traditions were "lesser stages"

- Reflected colonial attitudes justifying domination

- Imposed Western categories on all traditions

We study them to understand the history of Religious Studies, NOT because their conclusions are correct.

✅ What we learn:

Cross-cultural comparison (good method)

Attention to symbolism (good insight)

❌ What we reject:

Evolutionary hierarchies (ethnocentric)

"Primitive/advanced" language (colonial)

Applying Functionalist vs. Substantive

💬 Turn to a partner (3 minutes):

Think of a religious practice you know (prayer, meditation, pilgrimage, fasting, etc.).

Formulate:

1. One FUNCTIONALIST question (What does it DO?)

2. One SUBSTANTIVE question (What does it MEAN?)

Be ready to share with the class.

How Did Religious Studies Emerge?

From theology to academic discipline

The academic study of religion emerged as a distinct discipline in the 19th century.

Theology → Comparative Religion → Religious Studies

Before 19th Century:

Religion studied through theology (from within traditions)

19th Century: "Science of Religion" Emerges

Scholars began studying religion comparatively, applied social scientific methods

Key figures: Max Müller (philology), Cornelius Tiele (phenomenology)

20th Century: Institutionalization

Religious Studies departments separate from theology schools

Debates: Can you study religion "objectively"? Should you?

21st Century: Critical Turns

Postcolonial critique, attention to power/gender/race, digital religion

Method #1: Historical-Critical Approach

What It Is:

- Studies the process of a religion's beginnings, growth, diversity, decline

- Uses: archaeology, textual analysis, historical contextualization

- Treats religious texts as historical documents

Example Applications:

- Dating biblical manuscripts

- Tracing Buddhist text development across centuries

- Analyzing how Qur'anic interpretation changed over time

Strengths:

Grounds religion in concrete history; reveals how traditions change

Limitations:

Can miss what religion means to practitioners today

Method #2: History of Religions

(Religionswissenschaft)

What It Is:

- Studies religion as a social and cultural phenomenon

- Comparative approach: looks for patterns across traditions

- Interdisciplinary: anthropology, sociology, history, philology

Examples:

- Comparing creation myths across cultures

- Tracing how Buddhism adapted: India → China → Japan

- Analyzing how Christianity changed in new cultural contexts

Translation: German for “the scientific study of religion” (often rendered in English as Religious Studies).

This approach studies religions as human, historical, and cultural phenomena using tools from history, anthropology, sociology, and philology (language/text study).

Key idea: it aims to describe, compare, and explain religions without trying to prove or disprove their truth-claims (that’s theology or apologetics).

Why it matters: it helps scholars see patterns and changes across time and cultures—how traditions adapt, spread, and transform.

Method #3: Phenomenology of Religion

Core Principles:

1. Empathetic Standpoint

Describe religions in their own terms from practitioners' perspective

2. Bracketing (Epoché)

Temporarily suspend your own beliefs and judgments

3. Irreducibility of the Sacred

Religion cannot be fully explained by psychology, sociology, economics alone

4. Comparative Focus

Seeks universal or essential aspects of religious life

An approach that seeks to describe religions empathetically "in their own terms" from the standpoint of practitioners.

Key principles: Epoché (bracketing), empathy, irreducibility, comparison.

Major figures: Rudolf Otto, Gerardus van der Leeuw, Mircea Eliade, Ninian Smart.

Critiqued for potentially essentializing religion or smuggling in theological assumptions.

Greek philosophical term meaning "suspension" or "holding back."

In phenomenology: Temporarily setting aside your own beliefs, judgments, and assumptions to focus purely on describing phenomena as they appear.

Example: Don't ask "Is God real?" Ask "What is the experience of encountering God like for this practitioner?"

Phenomenology in Practice

Imagine: You're watching someone meditate.

Other Approaches Say:

Psychologist: "They're reducing anxiety through controlled breathing."

Sociologist: "They're performing group identity as a Buddhist."

Historian: "This practice developed in ancient India."

Phenomenologist Says:

"Wait—let's first understand what the meditator thinks is happening."

◆ What's their experience from the inside?

◆ What do they believe they're doing?

◆ How do they describe the goal/purpose?

The phenomenologist temporarily brackets external explanations to really listen to the practitioner's own perspective.

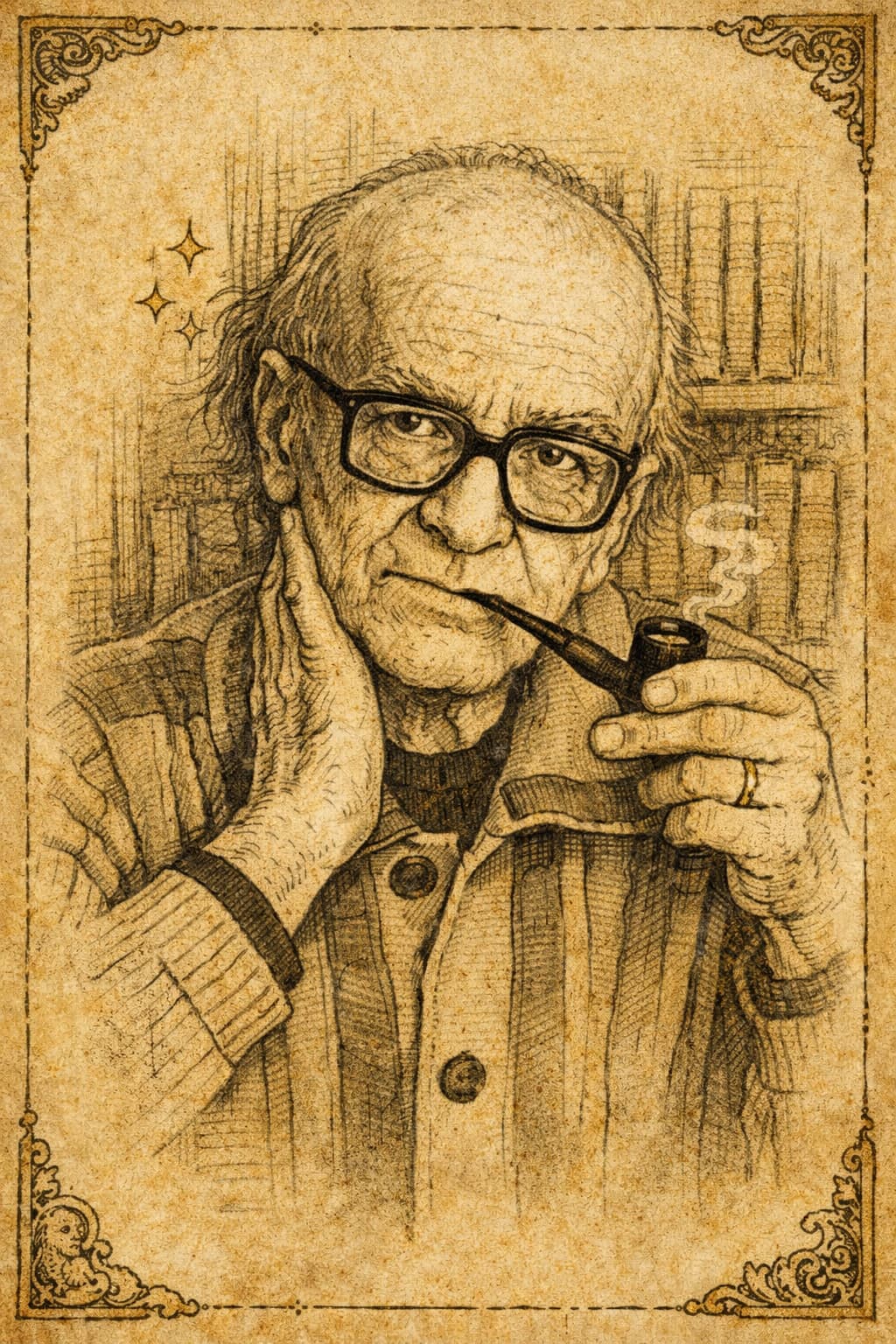

Mircea Eliade (1907-1986)

Key Phenomenologist

Eliade's Arguments:

- Irreducibility of the Sacred: Religious phenomena must be understood as uniquely religious

- Dialectic of Sacred/Profane: The transcendent manifests through ordinary phenomena

- Universal Symbolic Systems: Common symbols (water, sky, earth) appear across cultures

Major Works: The Myth of the Eternal Return (1949), The Sacred and the Profane (1959)

Romanian-American historian of religions (1907-1986).

Romanian historian of religions and University of Chicago professor. One of the most influential phenomenologists of religion.

Major works: The Myth of the Eternal Return, The Sacred and the Profane, Patterns in Comparative Religion.

Argued religion has irreducible essence (the sacred) appearing in universal patterns. Critiqued for essentializing and ignoring power/history.

Phenomenology: Strengths and Critiques

Strengths:

✅ Takes practitioners seriously on their own terms

✅ Attends to religious experience, not just structures

✅ Resists reductive explanations

✅ Comparative insights across traditions

Critiques of Eliade:

❌ Accused of "crypto-theology"—smuggling in religious assumptions

❌ May essentialize religion (assume universal core)

❌ Can ignore power dynamics, history, context

❌ "Bracketing" harder than it sounds

Contemporary Approach: Most scholars today use multiple methods—historical, sociological, phenomenological—recognizing each has strengths and limitations.

Critical Awareness

Examining our own tools

"Map Is Not Territory"

Jonathan Z. Smith wrote: "Map is not territory."

All our frameworks—"world religions," "myth," "ritual," "functionalism," "phenomenology"—are maps we've drawn to help navigate complex terrain.

The map is useful, but it's not the same as the actual territory.

As we study, ask: Who created this category? What does it highlight and hide? How might practitioners describe their tradition differently?

This methodological self-awareness separates academic study from tourism or prejudice.

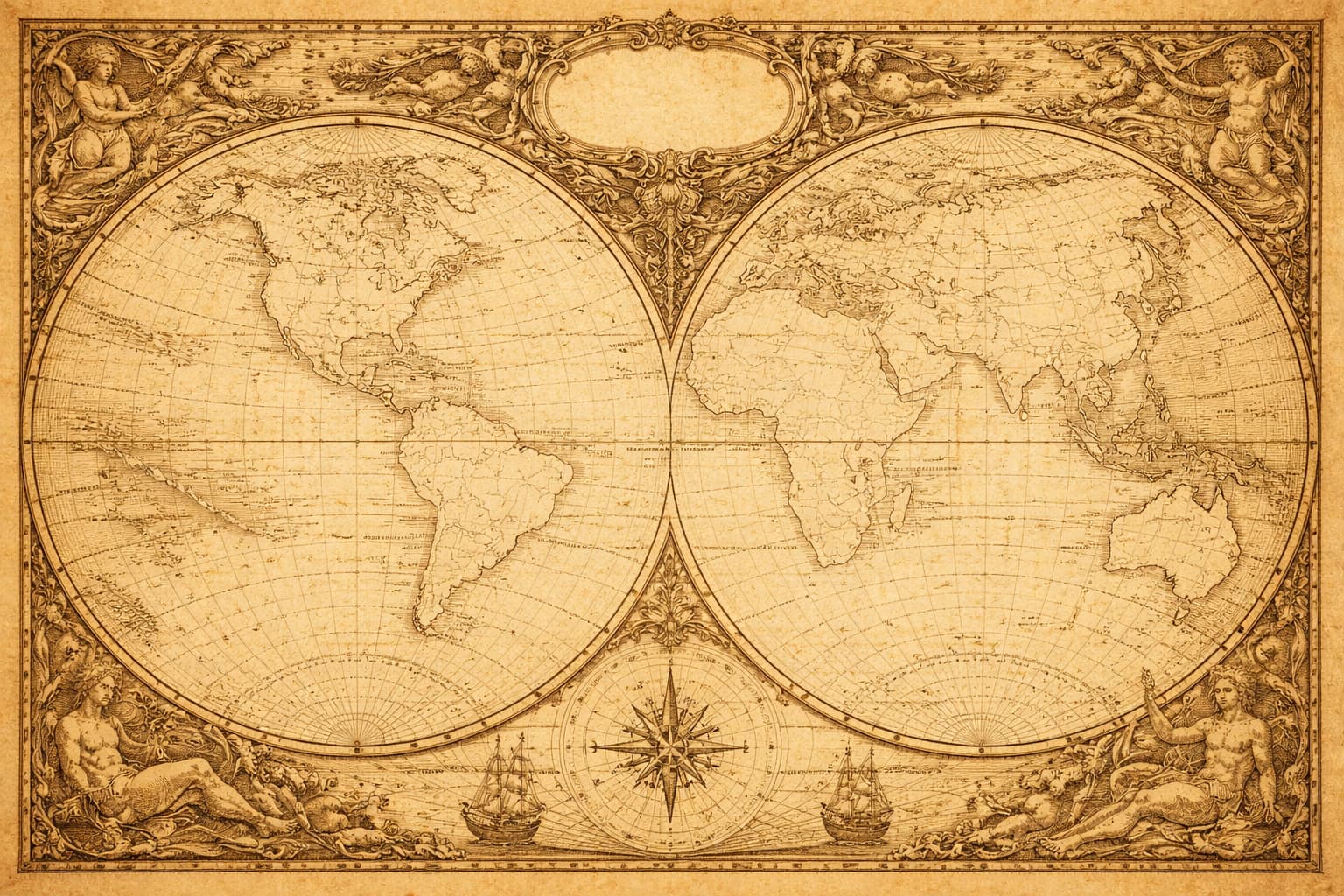

Historical map showing the constructed nature of cartography.

American historian of religions, University of Chicago. Known for deconstructing taken-for-granted categories in religious studies.

Major work: Map Is Not Territory (1978). Argued that "religion" is a scholarly construct, not a natural kind.

Influenced postmodern and critical approaches to religious studies.

Why "Maps" Matter Socially

Definitions of "religion" can shape real lives because institutions use them.

Examples of Power at Work:

- Governments decide what counts as a religion for legal recognition

- Schools, courts, prisons decide which practices get protected

- Media labels some groups "religion," others "cult," "superstition," or "culture"

Analytic move: Ask who benefits from a definition—and who gets excluded.

Chapter 1 Complete

But the learning? That’s just getting started.

What we did here was the classroom version of Religious Studies.

The real work begins when you walk out the door:

- Keep reading (the textbook has more depth than any lecture)

- Keep noticing (religion is everywhere—rituals, symbols, identity, power)

- Keep questioning (categories are tools… not truths)

Education doesn’t end at the edge of the classroom—

it begins there.

➜ Tap your right arrow key (or press Space) to continue.

There are more slides. More ideas. More.

Independent Study: Ethnography & “Lived Religion”

Not all religion lives in books. A lot of it lives in bodies, habits, spaces, and community life.

What Ethnography Does:

- Ethnography studies religion by observing and describing practices “in the wild”

- Focuses on lived religion (everyday religion as actually practiced)

- Attends to: ritual, material culture, emotion, community norms, identity, authority

Key move: Don’t assume the “official” version tells you what people actually do.

What to look for

- Who leads? Who follows?

- Repeated words, gestures, or sequences

- Objects used (books, candles, water, clothing, food)

- Space: where people stand/sit; boundaries

- Emotion: reverence, joy, awe, grief, calm

- Authority signals: titles, clothing, stage/altar, microphone

Independent Study Task (open)

A research method (common in anthropology/sociology) that studies people and cultures through observation, participation, interviews, and detailed description.

In Religious Studies: ethnography asks how religion is practiced, experienced, embodied, negotiated, and taught in real communities.

Strength: captures lived reality. Limit: your presence/assumptions shape what you notice.

A way of studying religion that emphasizes everyday practice over official doctrine.

Includes: informal rituals, family traditions, personal prayer habits, “folk” practices, online religious life, and local interpretations.

Key idea: religion is not only what a tradition says—it’s what people do with it.

These are for your own benefit: practice tools, deepen understanding, build confidence.

Not submitted. Not graded.

Step 1: Watch 8–12 minutes of a public religious event (livestream worship, festival video, temple tour, mosque khutbah clip, etc.).

Step 2: Write 8 observations that are concrete (what you saw/heard): actions, words, objects, space, roles, emotions.

Step 3: Write 2 questions:

• Functionalist: “What does this DO?” (effects on people/community)

• Substantive: “What does this MEAN?” (intentions/experience from insiders’ view)

Tip: Description first, interpretation second. That’s the ethnographic muscle.

Independent Study: Material Religion & Sacred Space

Religions don’t just live in minds—they live in objects, architecture, music, clothing, and ritual tools.

Key Concepts:

- Material religion studies how objects and spaces shape belief and practice

- Sacred space is made through boundaries, rules, and repeated ritual action

- Objects aren’t “mere symbols”—they often function as tools for devotion, identity, and community

Method move: ask what an object/space makes possible—and what it makes difficult.

Starter options

Prayer beads • Incense • Icon • Candles • Holy water • Altar • Sacred clothing • Pilgrimage route • Temple layout • Calligraphy • Chanting/music

Tip: pick something you can describe clearly in 1–2 pages.

Independent Study Task (open)

An approach that studies religion through physical culture: objects, images, architecture, clothing, food, sound, and bodily practice.

Key claim: material things don’t just represent religion—they help produce religious experience and social belonging.

A space experienced as set apart—created through boundaries, rules, stories, and repeated ritual actions.

Examples: temples, mosques, churches, shrines, pilgrimage routes, cemeteries, home altars, even certain online spaces.

Analytic question: Who controls the space, and what behaviors are expected inside it?

These are for your own benefit: practice tools, deepen understanding, build confidence.

Not submitted. Not graded.

Step 1: Choose ONE object or sacred space.

Step 2: Describe it clearly (what it is, where it appears, how it’s used, who uses it).

Step 3: Analyze it in three lenses:

- Function: What does it DO for individuals/community?

- Meaning: What does it MEAN to practitioners?

- Power/identity: Who is included/excluded by its use or access?

Tip: Treat objects/spaces as “evidence.” They are part of the tradition’s data.

Independent Study: Interpretation & Hermeneutics

You’ve seen historical-critical work (texts as historical documents). Another major toolkit is hermeneutics: how interpretation produces meaning.

Three Common Lenses:

- Historical: What did this mean in its original context?

- Literary: How does the text function as story/poetry/law?

- Community: How do practitioners interpret and apply it today?

Same passage, different “maps.” Your job is to identify the map—not just pick a winner.

Lens quick check

If the reader keeps saying…

- “In that time and place…” → Historical

- “Notice the imagery / structure…” → Literary

- “For believers today…” → Community

- “Who benefits from this reading?” → Critical

Independent Study Task (open)

The study of interpretation—especially how texts (and symbols) produce meaning.

In Religious Studies: hermeneutics asks how readers, communities, and contexts shape what a text is understood to mean.

Key point: meaning is not “free-for-all,” but it is also not automatic—interpretation has rules, traditions, and power dynamics.

These are for your own benefit: practice tools, deepen understanding, build confidence.

Not submitted. Not graded.

Step 1: Pick one short passage from a sacred text (or use one discussed in class/textbook).

Step 2: Find TWO interpretations of that passage (commentary, lecture, article, denominational explanation).

Step 3: Compare the “maps”:

- What question is each interpretation answering?

- What assumptions are driving the reading?

- What does each highlight—and what does it ignore?

- Label each lens (Historical / Literary / Community / Critical).

Tip: You’re practicing method recognition, not grading “who’s right.”

Independent Study: Religion in the Digital Wild

Religion doesn’t only happen in temples and texts. It also happens on screens: livestream worship, short-form sermons, online prayer requests, algorithm-shaped communities.

Three Questions for Analysis:

- Authority: Who counts as a teacher online—and why?

- Community: How do people build belonging without shared physical space?

- Ritual: What practices migrate online, and what changes when they do?

New “territory,” new “maps”: algorithms shape what you see, who you meet, and what feels “normal.”

Key term

Digital religion: religious life shaped by platforms, media formats, and algorithms.

Ethics: Public content only. Don’t name private individuals. Analyze—don’t mock.

Independent Study Task (open)

The study of religious practices and communities that exist online or are significantly shaped by digital media.

Key issues: authority, community formation, ritual adaptation, and platform power (algorithms, moderation, monetization).

Analytic twist: the platform isn’t neutral—it shapes what becomes visible and valued.

These are for your own benefit: practice tools, deepen understanding, build confidence.

Not submitted. Not graded.

Step 1: Find a religious community or teacher on a public platform (YouTube, TikTok, Instagram, podcast, livestream).

Step 2: Describe what you see (avoid “good/bad” at first): content, tone, symbols, language, practices.

Step 3: Analyze with four prompts:

- Authority: Who is trusted here—and why?

- Community: How do followers interact and belong?

- Ritual/practice: What is being taught or performed?

- Power/exclusion: Who might be pushed out or misrepresented?

Tip: Apply both questions: “What does this DO?” and “What does this MEAN?”

What Counts as Evidence?

✅ Good Evidence:

Primary sources:

Sacred texts, first-hand accounts, historical documents, ethnographic observations

Secondary sources:

Scholarly books, peer-reviewed articles, reputable news sources

❌ NOT Good Evidence:

"I think..." or "I feel..." (personal opinion without support)

"Everyone knows..." (unexamined assumptions)

Stereotypes from media or hearsay

Random websites without scholarly credentials

❌ Instead of:

"I think Buddhism is peaceful"

✅ Write:

"Scholar X argues that Buddhist ethics emphasize ahimsa (non-harm), as evidenced by texts such as the Dhammapada."

How to Engage Critically While Respecting People

You may encounter beliefs or practices you find strange, wrong, or troubling. That's okay.

❌ Instead of this...

"That's crazy/stupid/backwards"

"They're wrong"

"I can't believe anyone would..."

"That doesn't make sense"

✅ Try this...

"From an outsider's perspective, this seems..."

"A critic might argue..."

"This challenges my assumptions about..."

"This operates according to a different logic..."

✅ Analyze power dynamics, critique ideas with evidence, note contradictions, disagree respectfully

❌ Blanket dismissals, assuming your worldview is superior, reducing people to stereotypes

What We've Accomplished in Chapter 1

Foundations:

✅ "World religions" as constructed framework

✅ Identified our preunderstandings

✅ Adopted holy envy as approach

✅ Distinguished academic study from theology

✅ Recognized practice vs. belief emphasis

Content:

✅ Building blocks (myth, ritual, sacred, numinous)

✅ Ideal vs. lived religion

✅ Multiple definitions (no single answer!)

✅ Functionalist vs. substantive approaches

✅ Key methods (historical-critical, phenomenology)

Skills:

✅ Critical awareness of categories

✅ Respectful but analytical engagement

✅ Using evidence and course vocabulary

✅ Asking good questions from multiple perspectives

Contemporary:

✅ Digital religion

✅ Methodological self-awareness

✅ "Map is not territory"

You're now equipped to study specific traditions!