Through the Lens of War

Civil War Photography and the Making of Modern Memory

HIST 101

Before Photography: War as Art

War existed only through narrative memory

- Painting, sketches, written accounts, stories

- all filtered through artistic interpretation

- An artist chose what to include, what to omit, how to pose the figures, what expressions to give them.

1. Memory was narrative: flexible, interpretive, and everyone understood this.

Washington Crossing the Delaware, | Artist: Emanuel Leutze, 1851

The Death of General Warren at the Battle of Bunker's Hill, June 17, 1775 | Artist: John Trumbull, 1786

The Death of General Wolfe | Artist: Benjamin West, 1770

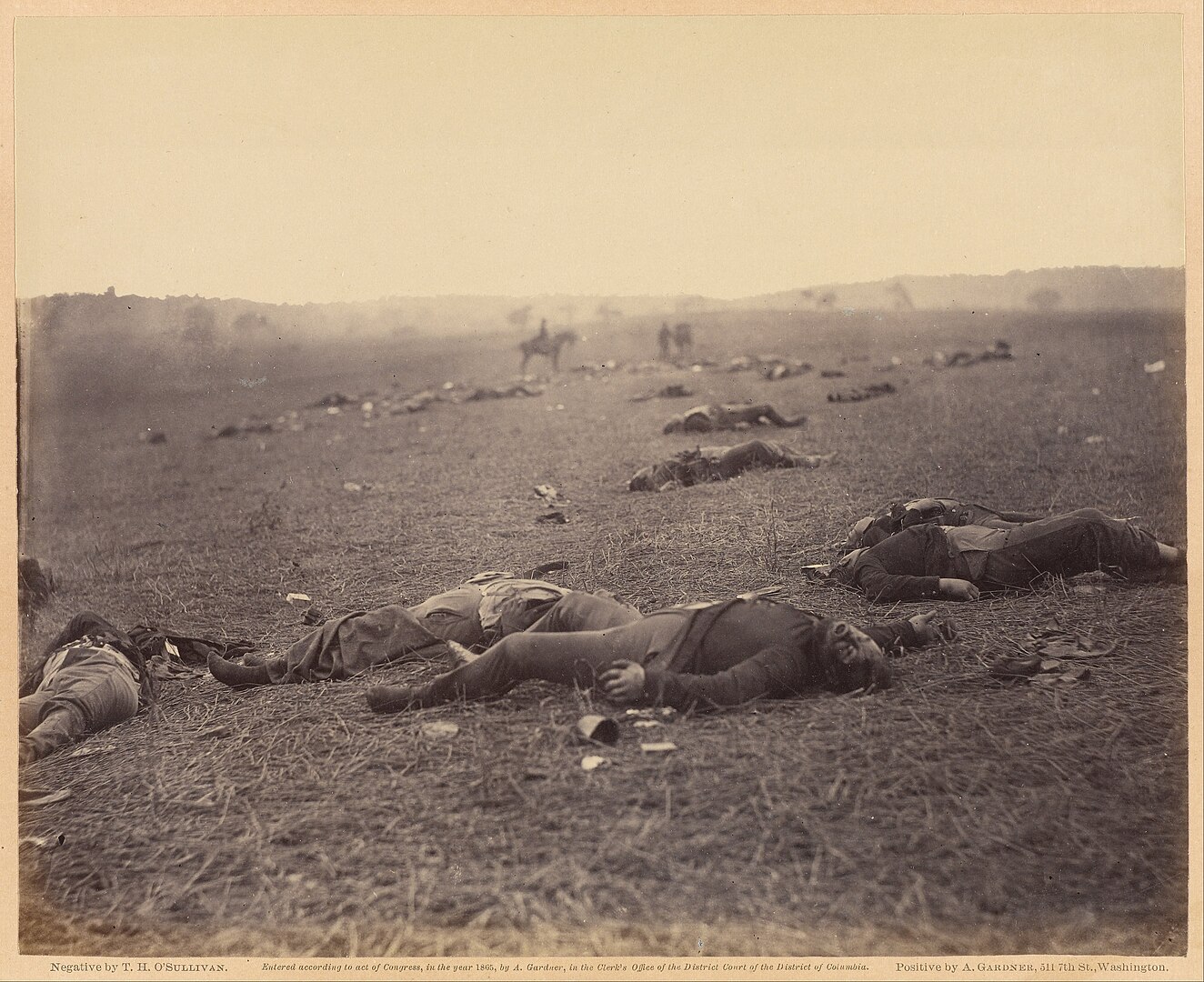

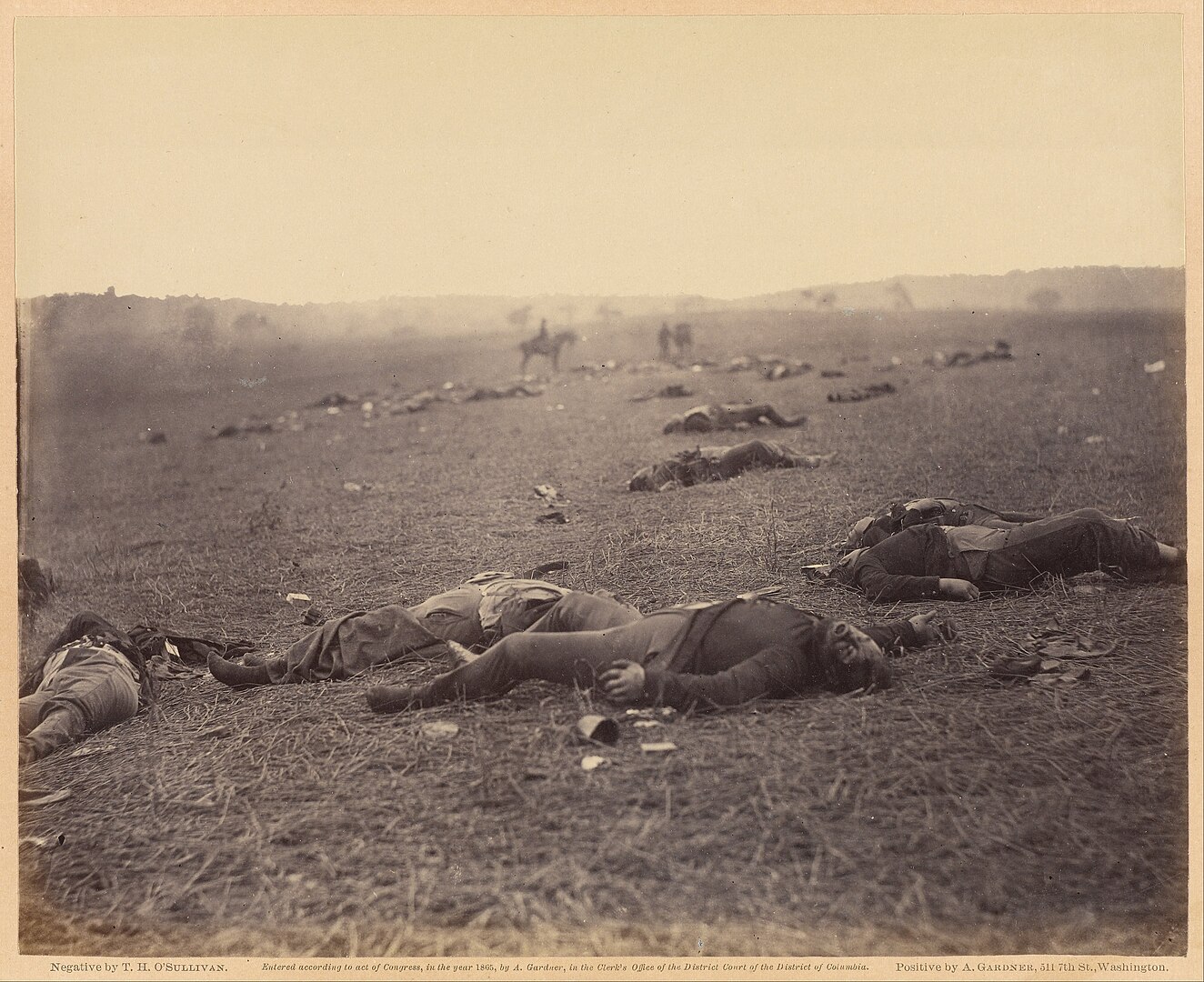

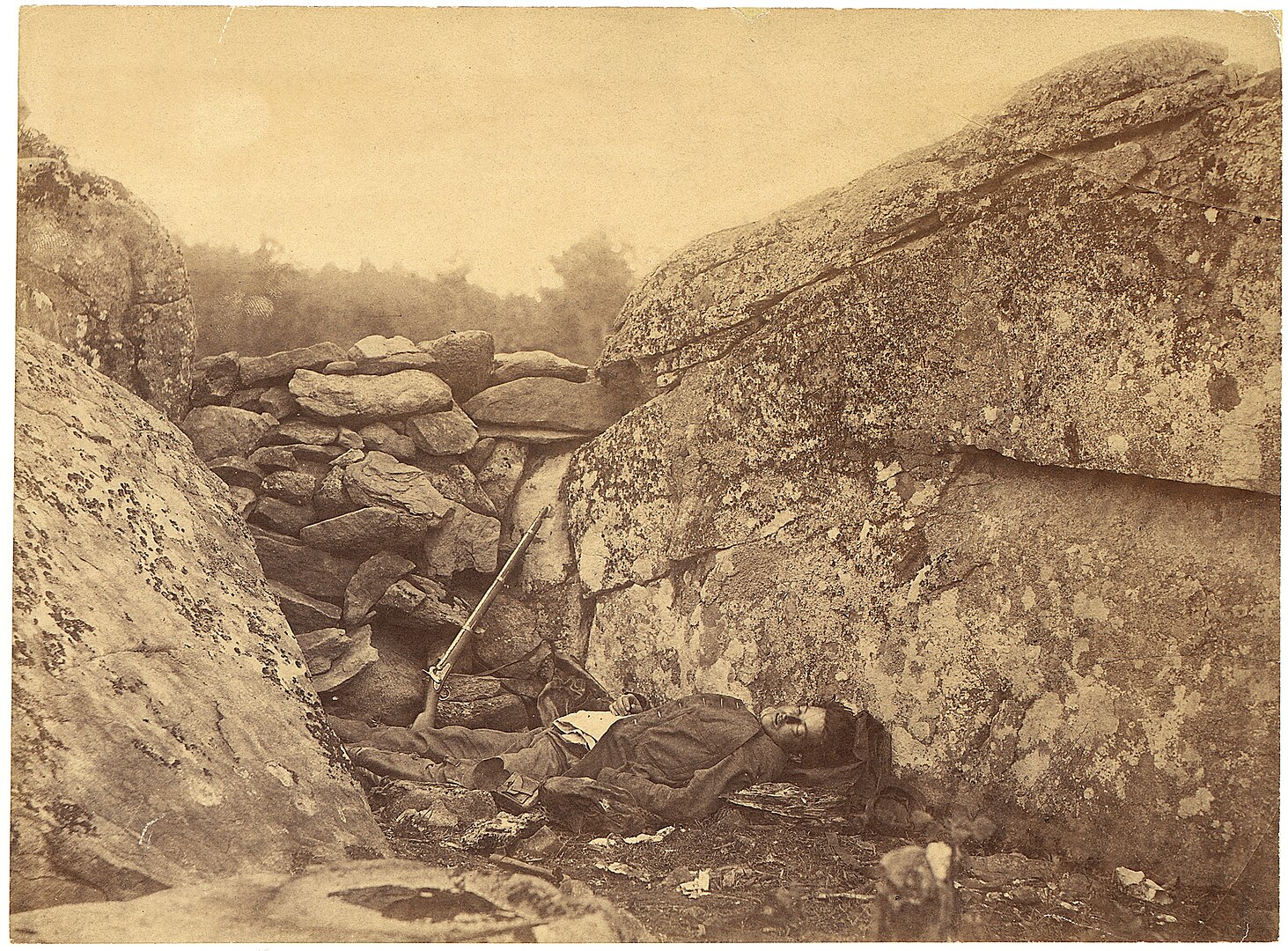

Alexander Gardner, "A Harvest of Death," Gettysburg, July 1863

Section I

The Camera Comes to War

Memory Arc:

Memory became visual (photographs) :

SEEMED objective but wasn't

Then Came the Camera

Alexander Gardner, "A Harvest of Death," Gettysburg, July 1863

- the camera was able to record what was in front of it

- It could not idealize, flatter, or misrepresent

- for the first time, seeing could be separated from human judgment

Or could it?

The Entrepreneur Photographers

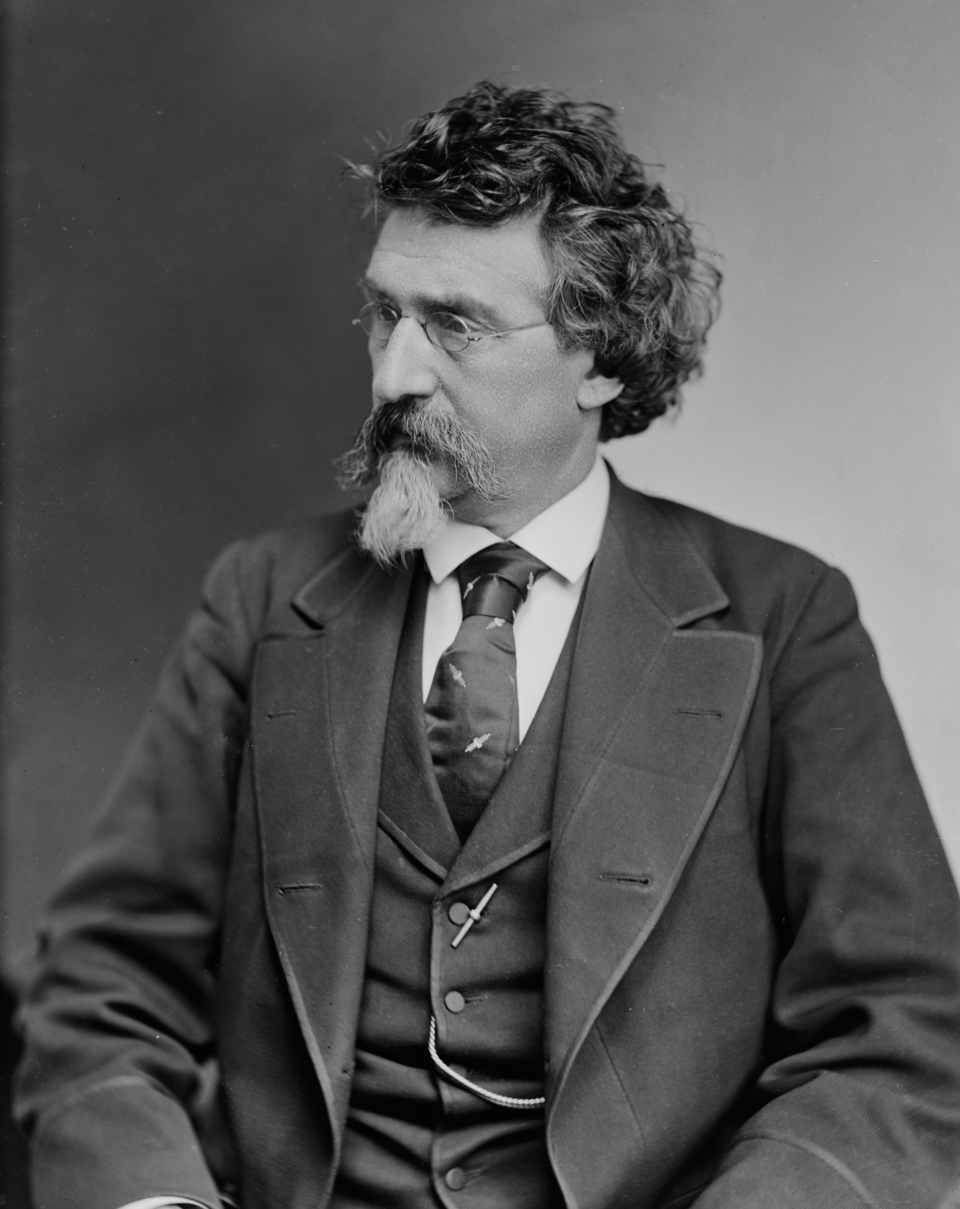

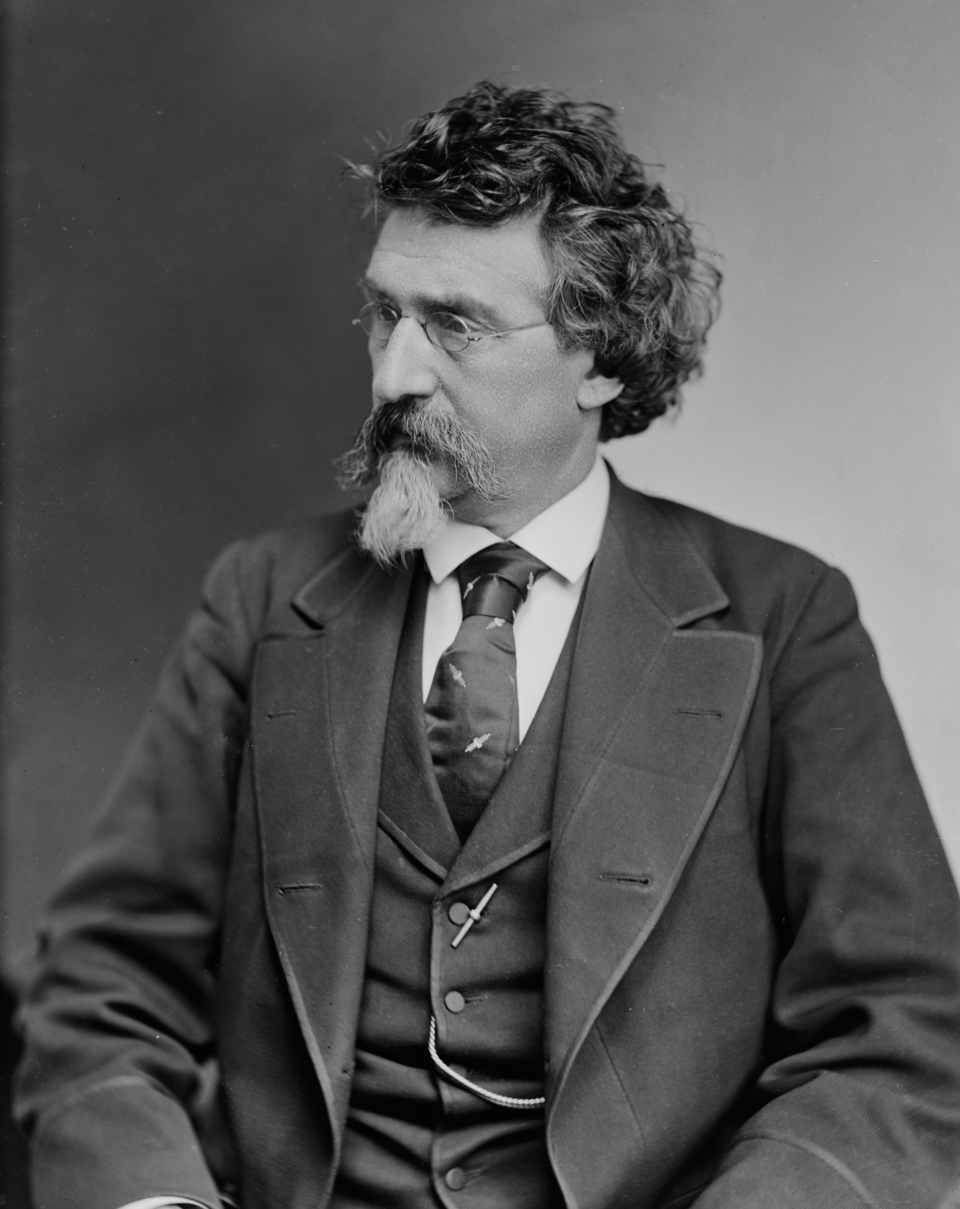

Mathew Brady

Famous portraitist, financed teams, claimed credit

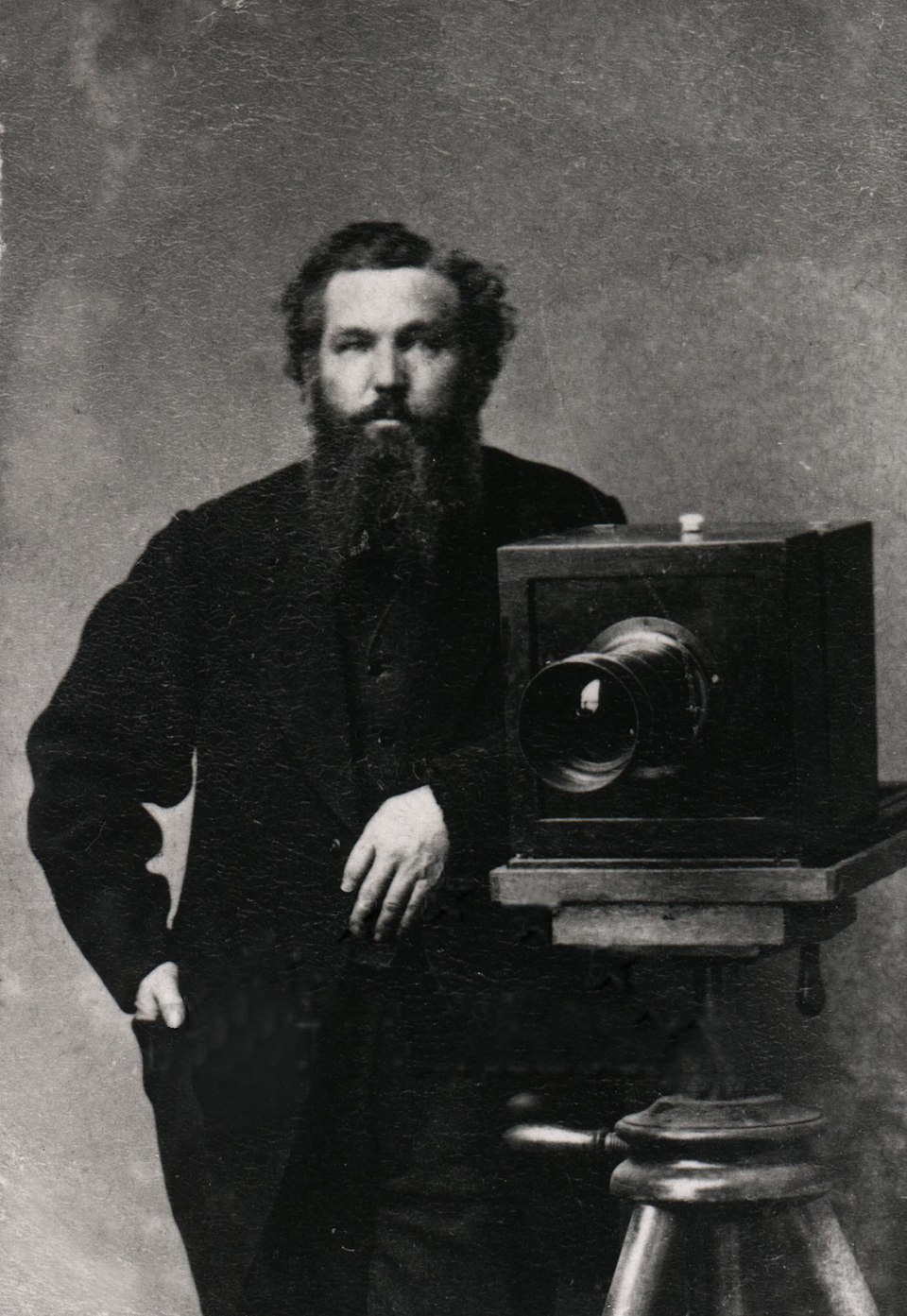

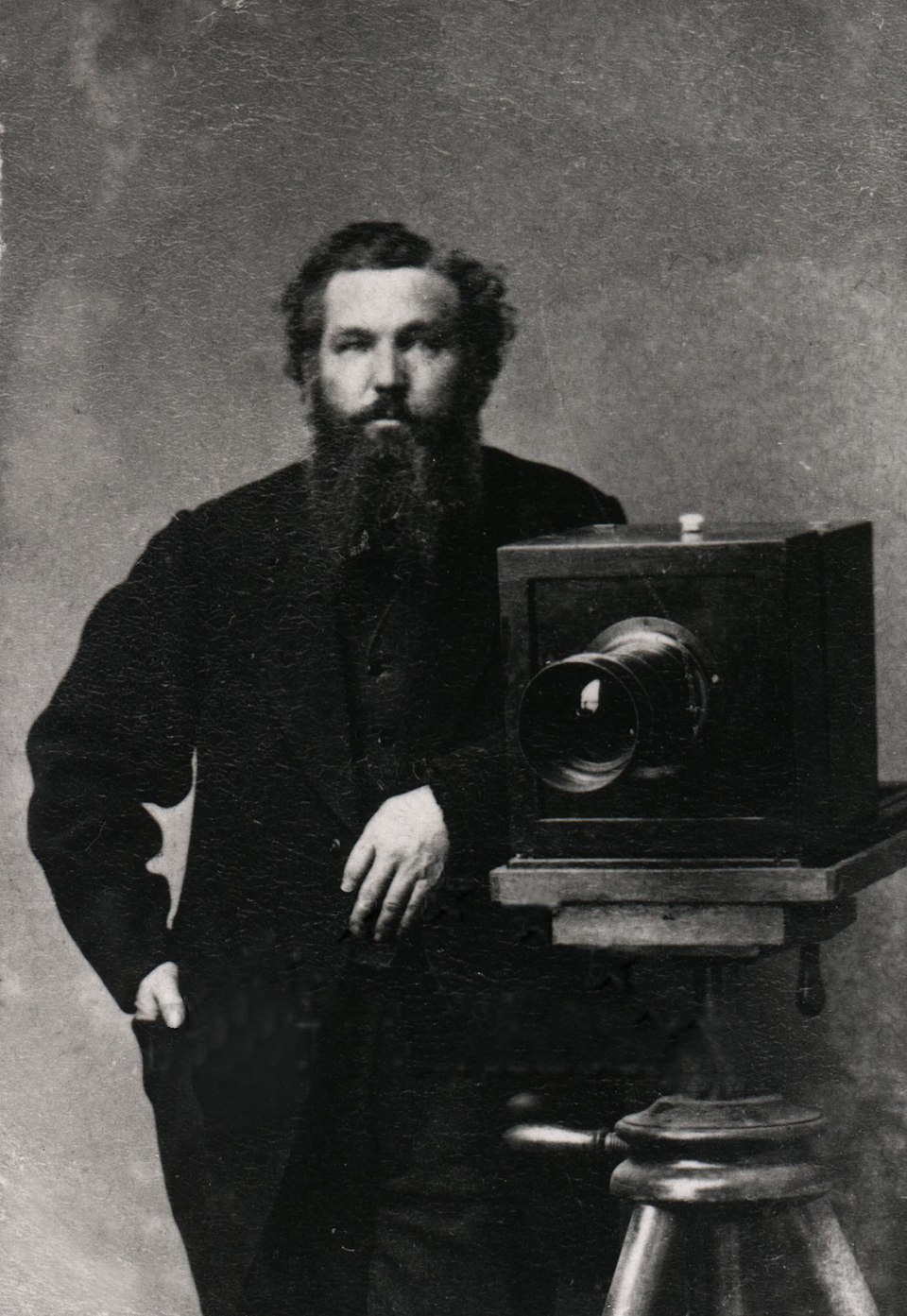

Alexander Gardner

Did the dangerous fieldwork

Timothy O'Sullivan

Did the dangerous fieldwork

Photography was an industry, not just documentation

How They Did It

Gardner's portable darkroom

Brady's "What-Is-It?" wagon

Photographer at work

What the Camera Could – and Couldn't – Show

- Wet-plate collodion required 5–15 second exposures

- You could photograph corpses — they held still

- You could photograph troops before or after battle!

- You could not photograph combat: charging soldiers, artillery fire, chaos of engagement

— everything blurred

General DeRussy at Arlington

Wet-Plate Collodion Process

The dominant photographic process of the 1850s–1880s. Here's how it worked:

- Coat a glass plate with collodion

- Sensitize it with silver nitrate

- Expose it while still wet

- Develop immediately in a portable darkroom

Imagine doing this in July heat, under artillery fire, surrounded by decomposing bodies. The physical demands were extraordinary.

The Silence of War

_LCCN2012647848.jpg)

Technology fundamentally shaped what Americans saw of the war:

- Aftermath, not action

- The dead, not the dying

- Silence, not screaming

Resulting images constrained by what technology allowed. Visual memory was already selective, even before human choices entered the picture.

Photography Promised Truth; delivered curated selections

The Camera's mechanical objectivity always shaped by human choices

- Which battlefield to visit

- Which angle to shoot from

- Who or what to shoot

- Which images to distribute, sell, or display

Photography promised objective truth—mechanical reproduction of reality. But visual memory was still shaped by human choices

The Photographers were not just documenting the war -- they were constructing a visual narrative of it

2. Memory becomes Visual: Seems objective but wasn't!

Section II

The Dead of Antietam

Memory Arc:

Memory became visual :

Civilians confront "objective" reality

The Battle of Antietam

- Fought on September 17, 1862 near Sharpsburg, Maryland

- Bloodiest single day in American history: ~23,000 casualties

- Union forces under McClellan halted Lee’s first invasion of the North

- Tactically inconclusive but a strategic Union advantage

- Gave Lincoln the position to issue the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation

Brady Sends Gardner to Antietam

- Mathew Brady ran the most famous photographic studio in the nation

- He believed the war must be visually documented for history

- Brady personally financed field teams—an enormous financial risk

- He dispatched Alexander Gardner to Antietam just days after the battle

- Brady aimed to create a sweeping visual archive under his own name

- Selection of these photos were displayed in Brady's New York Gallery as "The Dead of Antietam"

"The Dead of Antietam"

What Made Antietam Different

- Scale: ~23,000 casualties in a single day was incomprehensible

The photographs gave that number faces -- no longer an abstraction - Intimacy: These were not distant battlefield panoramas -- Gardner got close!

You could see buttons, belt buckles, facial expressions - Civilian confrontation: Before this - war's visual horror stayed at the front: Soldiers saw it; not civilians

Brady brought the horror to domestic space—a gallery on Broadway, surrounded by shops and theaters

Contemporary Reaction

Limits of Vision:

What Viewers Didn't See

What viewers didn't see matters almost as what they did!

- Most Antietam dead were already buried—Gardner arrived two days later

- His "harvest" was selective: mainly Confederate dead (Union burial details prioritized their own)

- Exhibition showed a skewed sample: More rebel dead than Union

- No photographs of

- field hospitals,

- surgery and amputations

- the wounded screaming in pain

Too blury; would not sell!

Photographs showed death as stillness -- almost peaceful -- not death as agony!

Democratic Witness

When Seeing Becomes a Moral Choice

Before photography, witnessing war required going to the battlefield.

After Antietam, images of the dead came directly into civilian life.

Viewers now faced a choice: confront the evidence or turn away.

To look was to know; thus, creating a new kind of civilian complicity.

You could no longer claim ignorance of the cost of war.

This is Democratic Witness: visual memory gave citizens direct access to war's reality, creating new obligations.

The camera forces a civic choice: seeing produces responsibility; avoidance preserves ignorance.

Democratic Witness

Definition: The principle that citizens in a democracy have both the right and the civic duty to observe, acknowledge, and publicly affirm truthful accounts of events carried out in their society—especially those involving state power or collective harm. Democratic legitimacy depends on shared visibility and public access to evidence, preventing truth from being controlled exclusively by elites or institutions.

What Democratic Witness Secures

- Legitimacy: Citizens believe a system is fair because they can see what’s happening—or see others who have witnessed it.

- Shared reality: Witnessing creates the common factual world democratic debate requires.

- Public oversight: Wrongdoing is harder to hide when ordinary people can document it.

- Moral reckoning: Witnesses can force society to confront wounds it might prefer to ignore.

The Camera Becomes

- a truth-telling device (imperfect, curated, but powerful)

- a moral summons to the viewer

- a tool for ordinary citizens to hold power accountable

Before photography, most “public truth” was textual and controlled. Photographs—especially documentary ones—dismantled that.

Democratic Witness Beyond Antietam

Seeing as Civic Reckoning

Forced Witnessing, 1945

After WWII, Allied forces required German civilians to walk through liberated camps.

Citizens confronted bodies, conditions, and material evidence of the Holocaust.

Purpose: break denial and create a shared factual foundation for postwar society.

Principle:

You cannot build a moral community on ignorance.

Night and Fog (1955)

Alain Resnais’s film stitches archival atrocity footage to quiet, present-day camp landscapes.

The viewer is drafted into witnessing—no longer able to deny or distance the past.

The film sustains public memory long after bodies are buried and ruins have decayed.

Principle:

Images make remembrance a civic duty.

Section IIB

The Intimate War

Memory Arc:

Visual memory is selective :

Whose faces survive depends on power

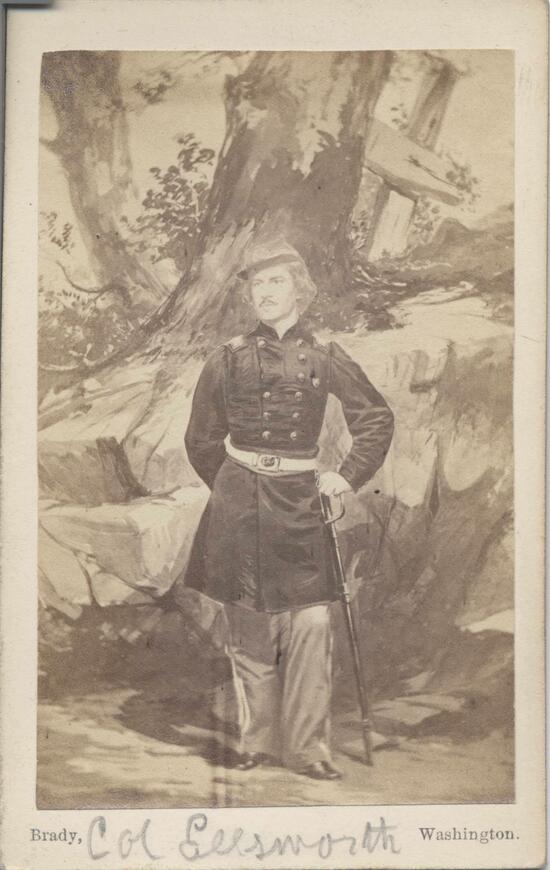

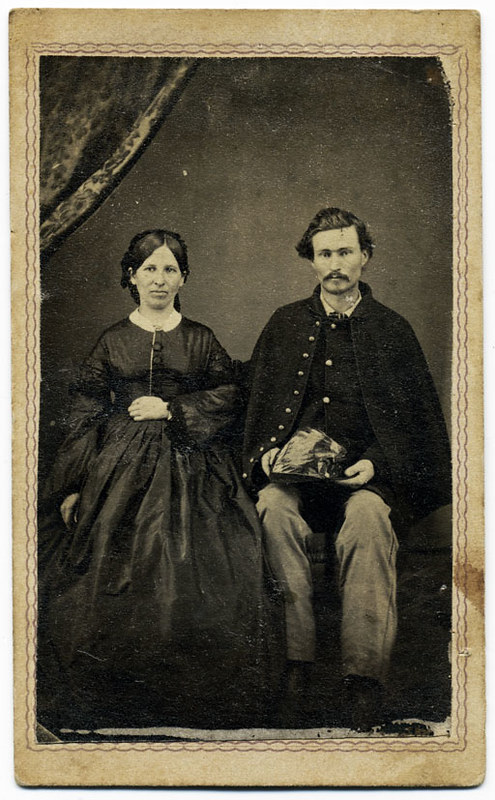

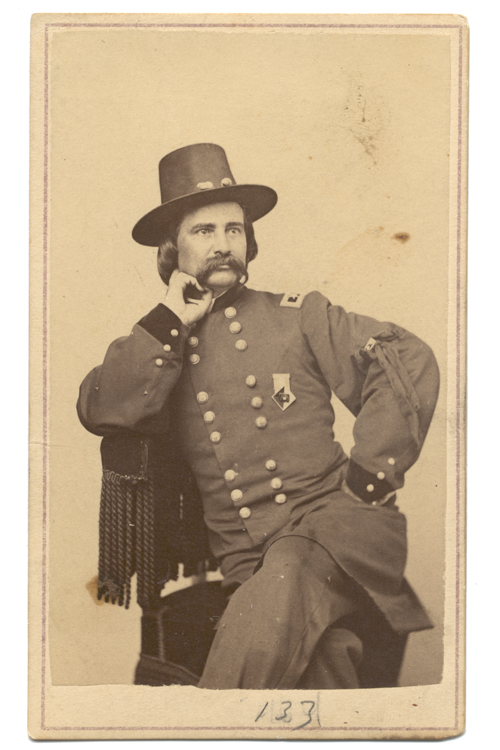

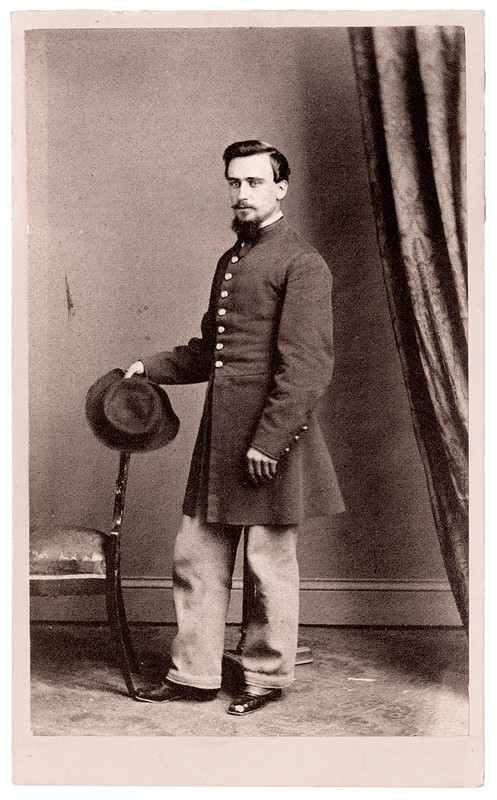

The Intimate War: Cartes-de-Visite

Cartes-de-Visite (kart-duh-vee-ZEET)

French for "visiting cards." Small albumen prints (2.5 x 4 inches) mounted on cardstock.

- Format: A multi-lens camera made 8 exposures on one plate, then cut apart—that's why they were cheap

- Cost: About 25 cents (down from several dollars for earlier processes)

- Scale: Millions produced during the war

- Function: Soldiers sent them home; families kept them in albums, lockets, Bibles. If a soldier died, the carte became a sacred relic.

Photography Enters the Home | Visual Memory becomes Personal

- Brady's gallery was public spectacle: crowds on Broadway gawking at the dead

- Cartes-de-visite was private intimacy: the photograph you held in your hand, studied alone, wept over.

- Transformed how Americans processed death: grief became visual and personal

The home became a memorial space, with photographs as secular relics - Who got photographed? Who Controlled the image?

Ethic of Framing: Who gets to decide what the camera sees and how its captioned?

And who controlled the images?

Visual memory was now tactile, portable, intimate. You could carry your dead with you. This was unprecedented.

Section III

Truth, Staging, and the Ethics of Seeing

Memory Arc:

Visual memory feels more authoritative

Staged images become "what happened"

Visual memory is selective

Whose faces survive depends on power

Alexander Gardner, "Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter," 1863