Harriet Beecher Stowe & Uncle Tom's Cabin

Goal: See how one novel helped shift public feeling about slavery and pushed the nation toward open conflict.

Welcome! This slide deck is your space to learn and explore at your own pace. As you move through each slide, click on the underlined words to see what they mean, and press L to open the notes. Stay curious—follow ideas that spark your interest, look up new terms, and see where your curiosity takes you!

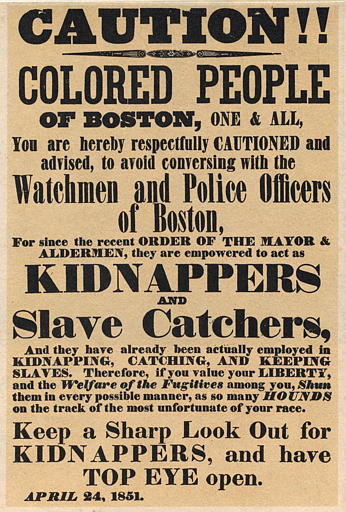

The 1850 Crisis

- The Fugitive Slave Act? forced Northerners to help return people who had escaped slavery, making them feel complicit.

- The law sparked moral outrage and turned personal conscience into a flashpoint.

- For many white Northerners, it was the moment slavery stopped being "someone else's problem."

For many Northerners, this was the first time slavery stopped being a distant issue happening “down South.” Suddenly, it was at their train stations, in their neighborhoods, and even in their courts. People who thought of themselves as law-abiding citizens were being told to ignore their conscience and enforce a system they found morally wrong. That’s why it caused such moral outrage — it wasn’t just about politics anymore, it was about personal responsibility and guilt.

This shift in feeling was huge. The Fugitive Slave Act forced people to decide what kind of nation they wanted to live in — one that obeyed unjust laws, or one that challenged them. Some Northerners began helping escapees through the Underground Railroad despite the risk. Others started speaking out, writing, and organizing in protest. In a sense, this law did the opposite of what it was supposed to: instead of preserving national unity, it made more people realize that compromise with slavery had a moral cost they couldn’t accept.

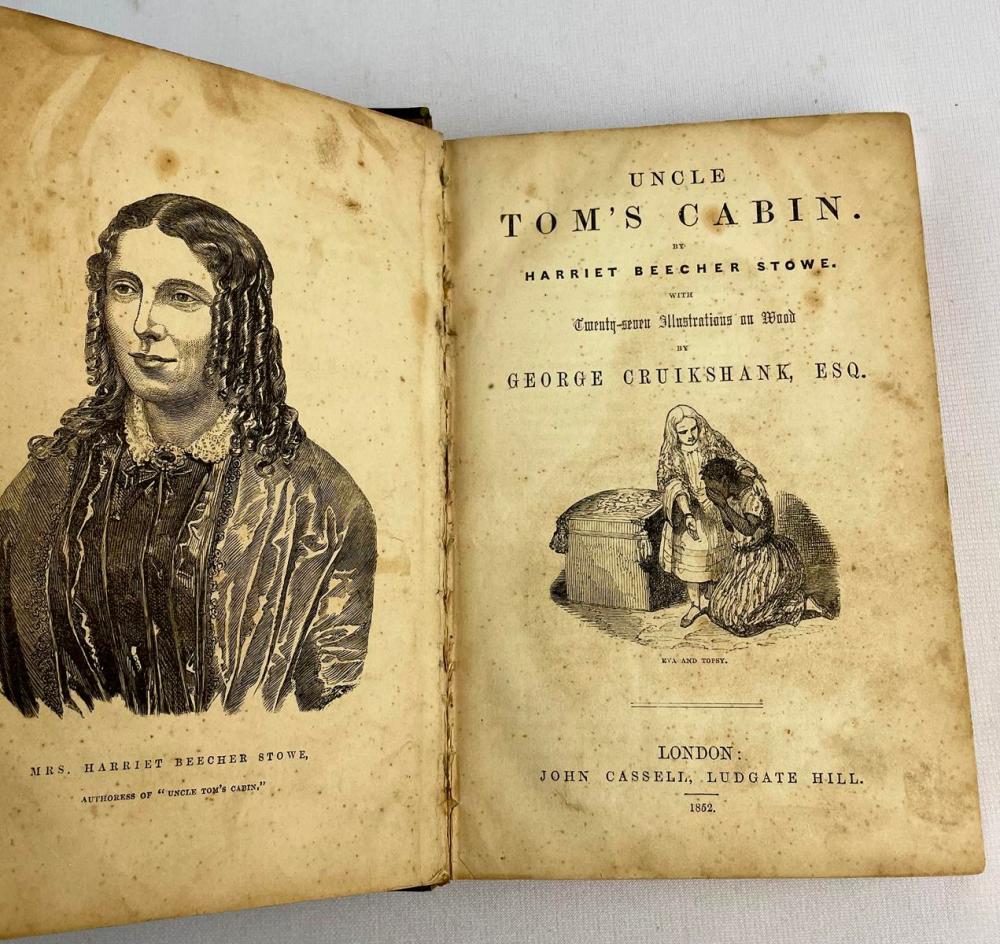

Who Was Harriet Beecher Stowe?

- Born into a famous minister's family—the Beechers shaped reform culture.

- Lived briefly in Cincinnati near the border, witnessing slavery's direct effects.

- Drew on her faith, family connections, and eyewitness accounts when writing.

Harriet Beecher Stowe came from a remarkable family—the Beechers were practically a reform movement of their own. Her father was a famous minister, and her brothers and sisters were active in education, religion, and social causes. So from an early age, she grew up surrounded by big moral debates about faith, justice, and reform. Writing about slavery wasn’t random for her—it was part of the world she’d always known.

When Stowe moved to Cincinnati, she lived right across the river from Kentucky, a slave state. That border setting made the issue of slavery real and immediate. She met people who had escaped slavery, heard their stories firsthand, and saw how the system reached into everyday life. Those experiences shaped her imagination and gave her the emotional truth that comes through in Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

When she sat down to write, Stowe drew on everything she had—her religious faith, her reform-minded upbringing, and the eyewitness accounts she’d collected. The result wasn’t just a novel; it was a moral argument told through storytelling. She believed that if people felt the pain of slavery the way her characters did, they would no longer be able to ignore it.

Writing Uncle Tom's Cabin

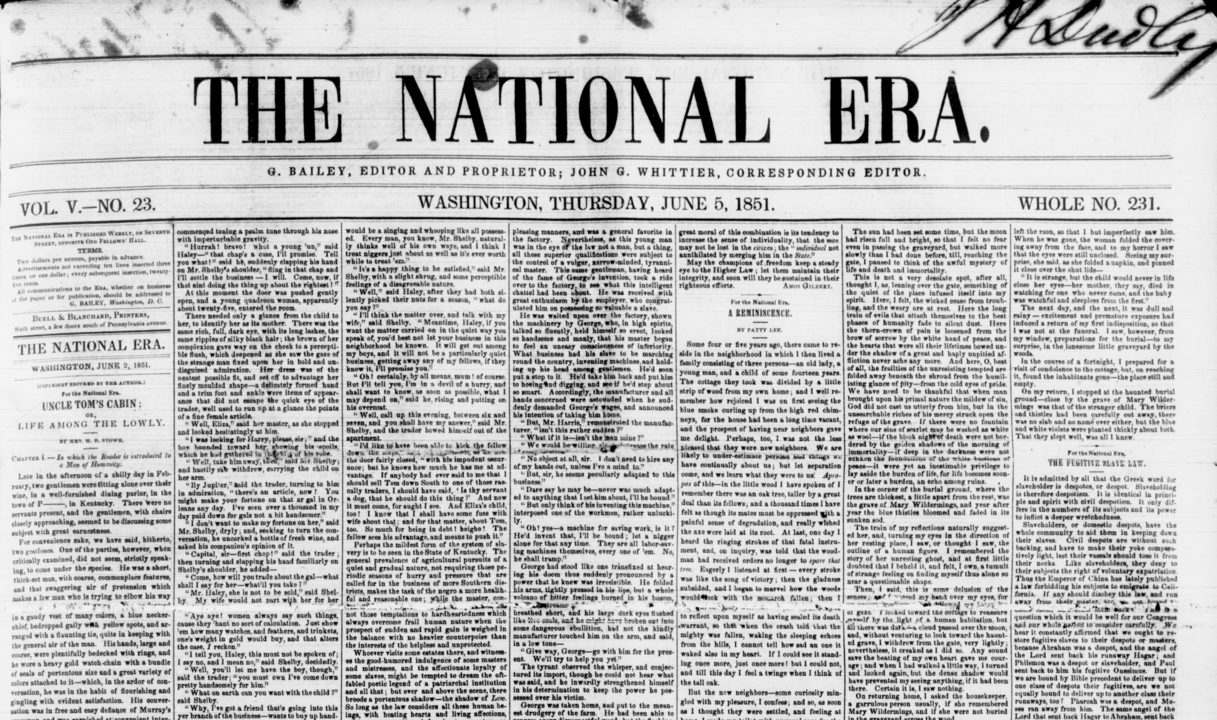

- First serialized in the National Era? (1851–52), a weekly abolitionist paper.

- Published as a book in 1852, selling over 300,000 copies in the U.S. in its first year.

- Stowe said she was inspired by a vision during church—she believed God directed her pen.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin didn’t start as a book—it began as a weekly story in the National Era, an abolitionist newspaper published in Washington, D.C. Between 1851 and 1852, readers followed the story in short installments, almost like a TV series of its time. The emotional impact was immediate, and by the time the full novel came out in 1852, it became a publishing sensation, selling over 300,000 copies in its first year in the United States alone.

Stowe often said the idea for the book came to her during church, almost like a vision. She believed that God was guiding her hand as she wrote. That sense of divine mission gave the novel its emotional intensity—it wasn’t just meant to entertain but to convict the conscience of its readers. She saw her work as both art and activism, something that could move hearts where political arguments had failed.

Why the Story Hit So Hard

- It used sentimental fiction?—emotional storytelling that made readers feel the injustice.

- Characters like Uncle Tom and Eliza became symbols; their suffering felt personal.

- The novel invited white readers to imagine themselves in the place of the enslaved.

Part of what made Uncle Tom’s Cabin so powerful was its use of sentimental fiction—writing designed to pull at the reader’s emotions. Stowe wanted her audience to not just understand slavery as a political issue, but to feel its cruelty. The book’s emotional tone wasn’t accidental; it was meant to make readers cry, empathize, and question how such suffering could exist in a so-called Christian nation.

Characters like Uncle Tom, Eliza, and little Eva became more than just figures in a story—they turned into moral symbols. Readers followed their struggles, heartbreaks, and acts of courage as if they were real people. Through them, Stowe created an emotional bridge between enslaved people and white Northern readers who had never seen slavery firsthand.

In doing so, the novel asked its audience to imagine themselves in the place of the enslaved—to see what it would feel like to have one’s family torn apart or to be treated as property. That act of imagination was revolutionary. It made empathy a form of activism, and for many readers, once they felt that connection, they couldn’t go back to indifference.

An Instant Phenomenon

- Became the best-selling novel of the 19th century after the Bible.

- Theatrical adaptations toured constantly, reaching people who never read books.

- Everyone from politicians to preachers had to respond—it forced conversation.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin exploded in popularity. After the Bible, it became the best-selling book of the entire 19th century—a cultural event that reached far beyond the page. People everywhere were talking about it, quoting it, and arguing over it. It wasn’t just a novel anymore; it was part of the national conversation.

The story spread even further through stage adaptations called “Tom Shows.” These theatrical versions toured constantly, performing in towns big and small. Many people who never read the book still experienced the story in theaters, where its emotional power played out live. In some ways, the plays had an even bigger impact because they made the story visual and unforgettable.

Politicians, preachers, and newspaper editors all felt the ripple effect. Everyone had to take a position—whether to defend the book, denounce it, or use it to make a point about slavery. In that sense, Uncle Tom’s Cabin didn’t just tell a story; it created a public debate that crossed class, region, and even national boundaries.

Changing Minds in the North

- Many Northerners who weren't committed abolitionists began questioning slavery.

- The book made slavery feel morally intolerable, not just politically inconvenient.

- It turned abstract policy debates into stories about families torn apart.

Before Uncle Tom’s Cabin, many Northerners didn’t see slavery as their responsibility—it was something happening far away in the South. The novel changed that. It made readers face the human side of slavery through powerful stories about love, loss, and injustice. Suddenly, what had been a political issue became a personal one.

For people who weren’t committed abolitionists, the book was eye-opening. Stowe’s characters—families torn apart, parents fighting to protect their children—made slavery feel morally unbearable. It was no longer just about laws or compromises; it was about real people and real suffering.

That shift in feeling was crucial. By bringing the pain of slavery into Northern living rooms, the novel made neutrality impossible. Readers started asking themselves hard questions about what kind of nation they were part of—and whether their silence made them complicit.

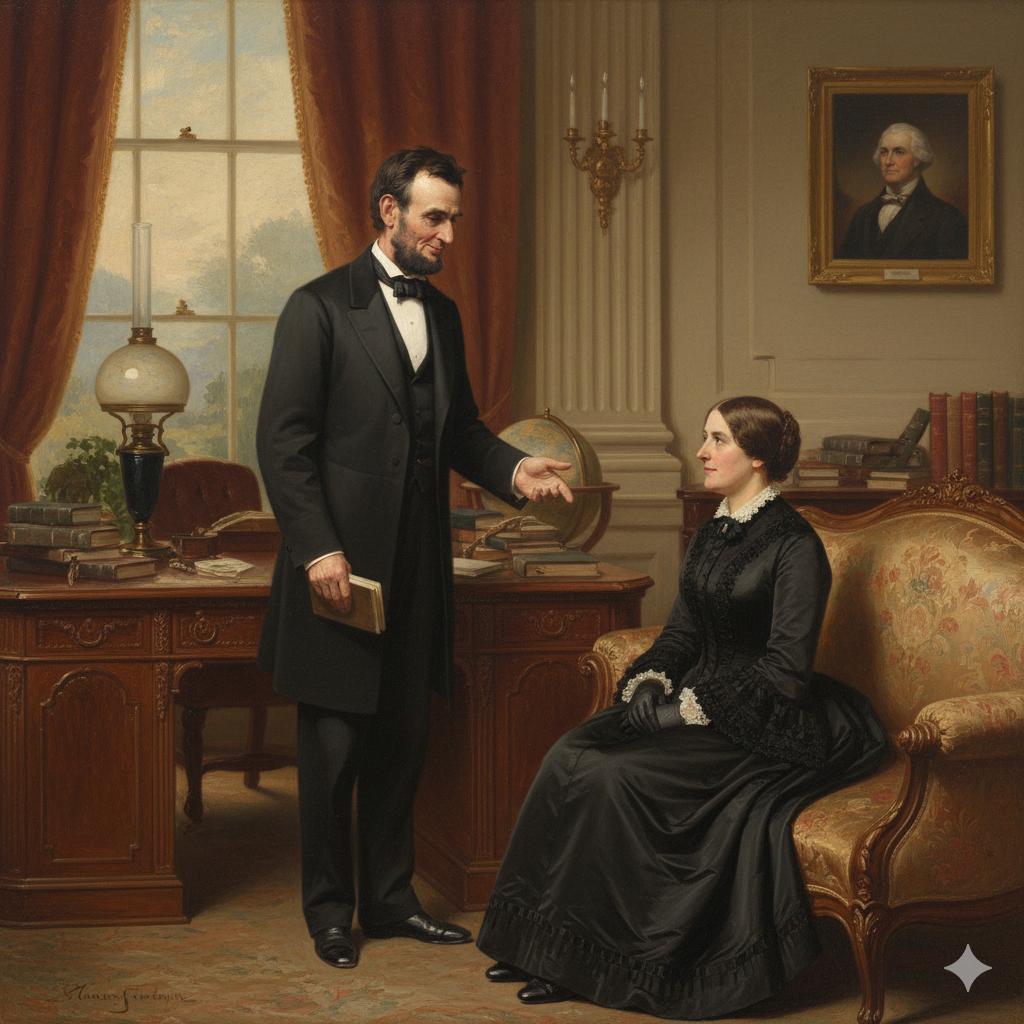

The Famous Line

- Lincoln supposedly greeted Stowe with: "So you're the little woman who wrote the book that made this great war!"

- The story is likely exaggerated or invented, but it captures a real truth.

- The novel helped prepare the cultural ground for conflict over slavery.

According to a famous story, when Abraham Lincoln met Harriet Beecher Stowe, he greeted her by saying, “So you’re the little woman who wrote the book that made this great war!” It’s one of those lines that’s probably too perfect to be true—but it stuck, because it captured what people already believed about the novel’s influence.

Whether Lincoln actually said it or not, the story reflects a real truth: Uncle Tom’s Cabin helped prepare the cultural ground for conflict. It didn’t cause the Civil War, but it made it harder for Americans to pretend that slavery could be ignored or endlessly compromised over. The book changed how people saw the moral stakes.

By the time the war began, Stowe’s story had already reshaped public feeling. It made readers view slavery not just as an economic or political issue, but as a test of national conscience. So even if the quote is apocryphal, its meaning endures—the power of a story to move hearts can end up moving history too.

Southern Critiques & "Anti-Tom" Novels

- Southern critics said Stowe exaggerated and ignored "kind" masters.

- Pro-slavery writers answered with Anti-Tom fiction? that defended slavery.

- The dispute exposed a deeper divide over whose stories counted as "truth."

Southern critics reacted fiercely to Uncle Tom’s Cabin. They claimed Stowe had twisted the truth—portraying only the worst examples of slavery and ignoring what they called the “kindly, paternal” relationships between masters and enslaved people. Many accused her of having no firsthand knowledge of plantation life, dismissing her as a Northern woman who didn’t understand the South’s “real” culture.

In response, pro-slavery writers began publishing what became known as “Anti-Tom” novels—stories meant to set the record straight from the Southern point of view. Among the most popular were Aunt Phillis’s Cabin (1852) by Mary Eastman, The Planter’s Northern Bride (1854) by Caroline Hentz, and Uncle Robin, in His Cabin in Virginia, and Tom Without One in Boston (1853) by J.W. Page. These books portrayed enslaved people as loyal, content, and dependent, while painting abolitionists as dangerous meddlers who stirred up unrest.

The clash between Tom and Anti-Tom novels showed how divided the nation had become—not just politically, but morally and emotionally. Both sides were using fiction as a weapon to define “truth.” For one audience, Stowe revealed the human cost of slavery; for the other, her story was seen as a threat to their entire way of life.

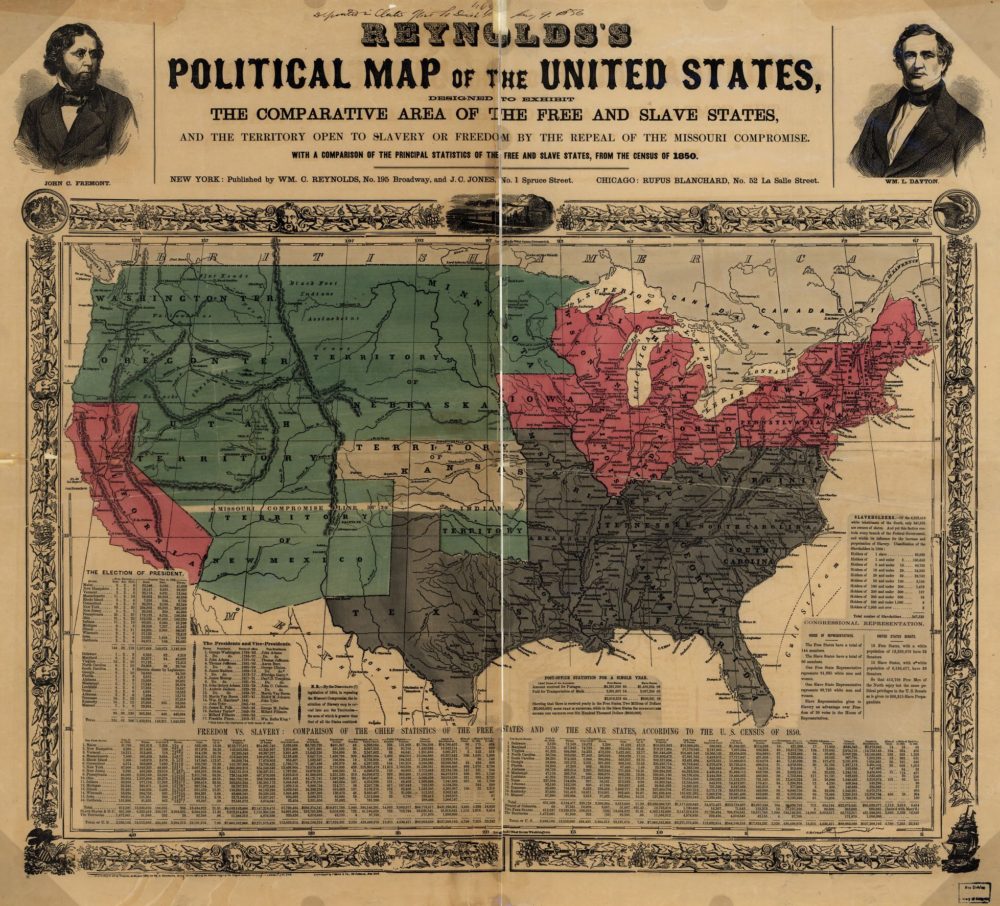

Across the Atlantic

- Translations carried the story across Europe, adding foreign sympathy to the anti-slavery cause.

- Stowe's fame turned American slavery into a global moral question.

- The novel helped frame the conflict as freedom versus oppression, not just North versus South.

The novel didn’t just stay in the United States. It crossed the Atlantic and became a phenomenon in Europe too. For instance, the first London edition of Uncle Tom’s Cabin appeared in May 1852 and sold about **200,000 copies** in its first run.

By the mid-1850s, the book had been translated into dozens of languages. One source notes that by 1857 more than two million copies had been sold worldwide. These translations carried the story—and its moral message—into foreign homes, turning American slavery into a subject of global concern.

What this meant for the U.S. debate was big: the novel helped frame the struggle not just as a regional conflict (North vs. South) but as a question of **freedom versus oppression** on a global stage. Readers abroad wondered how a republic that prided itself on liberty could allow human bondage—and that external scrutiny added pressure at home.

From Feeling to Fracture

- The novel made slavery a household conversation that people could no longer dodge.

- By shifting hearts, it made old compromises feel morally thin and unsatisfying.

- Many Americans began to see slavery as a national sin that demanded decisive change.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin turned the question of slavery into something people could no longer avoid. Before its publication, many Americans—especially in the North—treated slavery as a distant political issue. Stowe’s novel changed that by bringing the suffering of enslaved people into homes, churches, and parlors. It made slavery part of everyday conversation, something families debated around the dinner table.

That emotional awakening had real political consequences. By making readers feel the injustice, the novel made old compromises—like the Missouri Compromise or the Fugitive Slave Act—seem morally hollow. The story didn’t offer policy solutions; it changed people’s sense of right and wrong. Once that happened, the old political balancing acts no longer satisfied the moral urgency many now felt.

In this way, Stowe’s book helped push the nation from discomfort to confrontation. Many Americans began to see slavery not as someone else’s problem, but as a national sin that demanded action. That moral clarity helped prepare the ground for the political fractures—and ultimately, the war—that followed.

Key Terms — Click the ? for Definitions

Fugitive Slave Act?

Law

•

Sentimental Fiction?

Genre

National Era?

Press

•

Anti-Tom Novels?

Counter-Literature