Staging America:

Performance, Race, and Identity

Lecture 3

HIST 101: American History to 1865

←: Previous slide

↑↓: Scroll slide content

PgUp/PgDn: Previous/Next slide

Home: First slide

End: Last slide

F: Fullscreen

Esc: Overview mode

S: Speaker notes

?: Help menu

B or .: Pause (blackout)

Alt+Click: Zoom

The Creation of Leisure Time

Pre-1815: Traditional Work Patterns

- Seasonal rhythms governed agricultural work

- Task-based labor in artisan shops

- Work and life intermingled

- No clear division between "work time" and "free time"

Post-1815: Industrial Time

- Factory bells regulate the working day

- Wage labor creates fixed schedules

- Separation of work time from free time

- The working day creates its opposite: Leisure Time

Structured Time Off:

- Sundays (Sabbath observance)

- Evenings after work

- Saturday half-holidays (emerging practice)

New Question: What do you do when you're not working?

The Middle Class and Respectable Recreation

The New Middle Class

Clerks, shopkeepers, small manufacturers, professionals

Leisure time and discretionary spending power

Leisure as Status Marker

How you spend your free time signals who you are

Leisure becomes a way to perform and display middle-class identity.

Professional ideal: an antebellum doctor, c. 1840s.

The Feminization of Respectability

Middle-class women became powerful symbols of moral refinement.

- Visibility in public space became part of performing respectability.

- Women's taste shaped the boundary between "refined" and "vulgar."

- Leisure became a language of virtue as much as class.

Respectability performed in public: women at a museum.

Popular "Improving" Amusements

- Museums (natural history, curiosities)

- Moral lectures and lyceums

- Theater (the "right" kind—respectable venues)

Affordability

- Barnum's Museum: ~$0.25 admission

- Theater galleries: $0.50–$1.00

Geography of Respectability

Broadway Theaters

Upscale venues catering to middle-class tastes and values

Astor Place Opera House

Elite uptown venue symbolizing refined culture

Respectable recreation fused class aspiration with moral performance—on public display.

The Working-Class City: Conditions

Immigration Wave

Massive waves of Irish and German immigrants crowd into cities; See Chapter 14

Working Conditions

- Factory workers: 12–14 hour days, dangerous machinery

- Dockhands: Heavy physical labor, irregular employment

- Day laborers: Casual work, no job security

- Low wages, no benefits

- Child labor common

Living Conditions

- Overcrowding: Multiple families per room

- Slums: Poor sanitation, disease

- Tenement buildings with no running water

- High mortality rates

The Working-Class City:

Bowery · Fire Companies · Five Points

The Bowery

- Visible working-class culture

- Bowery Theatre: 12¢ tickets (affordable)

- Gangs & swagger: The "Bowery B'hoy" style

Fire Companies

- Volunteer brigades: civic service + identity

- Ward politics: ties to Democratic machines

- Masculine performance: courage, rivalry

Five Points

- Infamous slum in middle-class imagination

- Underground amusements: cockfights, dance halls

- Community & survival: families, mutual aid

The Hunger for Spectacle

Concentration of people in cities produces unprecedented demand for novelty and sensation

Newspapers and posters saturate public space; the city itself becomes a theater

Citizens perform their identity through choices of amusement—where you go and what you see defines who you are

Americans across classes crave spectacle but disagree on what forms are legitimate

Setting the Stage:

The Urban Public Sphere

The City as Theater

Media Turn Streets into Stages

Colorful advertisements plaster walls and buildings

Daily coverage of theatrical performances, scandals, and sensations

Walking Broadway or the Bowery means encountering performance at every turn

Urban space becomes a place to see and be seen

The city itself is theatrical—everyone is both performer and audience

The Public Sphere Becomes Performative

Traditional Ideal of Public Sphere

Rational debate in coffeehouses, salons, and through newspapers

Citizens participate through reading and reasoned discussion

Enlightenment model: Ideas triumph through logical argument

Structural Transformation: Democracy as Spectacle ℹ️

From rational debate toward spectacle and display

- Democracy means having the right to watch, judge, and participate in public amusements

- Citizens act by seeing and being seen, not just by reading and debating

- Identity is performed through your choice of amusement and your physical presence

New Rules of Citizenship

Participating by attending, watching, and judging public entertainment

Your identity is performed through where you go and how you behave there

Different entertainment venues = different claims about who represents "the people"

Public culture becomes contested terrain for representing "the people"

Habermas: Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere (1962)

Habermas and The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere

Jürgen Habermas's The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere (1962) is a landmark work in political theory and sociology that traces the rise and fall of what he calls the "bourgeois public sphere" in 18th-century Europe.

Habermas describes the public sphere as a realm between private life and state authority where citizens gather—in coffeehouses, salons, and through newspapers—to rationally debate matters of public concern. This space was revolutionary because people could discuss politics and hold power accountable through reason and argument, not social status.

The transformation Habermas tracks is essentially a decline: as mass media and consumer culture emerged in the 19th and 20th centuries, this rational-critical debate gave way to passive consumption and manipulation. Public discourse became dominated by advertising, entertainment, and manufactured opinion rather than genuine deliberation. Citizens became consumers, and the public sphere lost its critical edge.

The book's influence is enormous—it's foundational for understanding democracy, media, and civil society. Critics have challenged Habermas for idealizing the past and ignoring how the "public sphere" excluded women, workers, and minorities. But his core insight—that democracy depends on spaces for free, rational public conversation—remains vital for thinking about everything from social media to political polarization today.

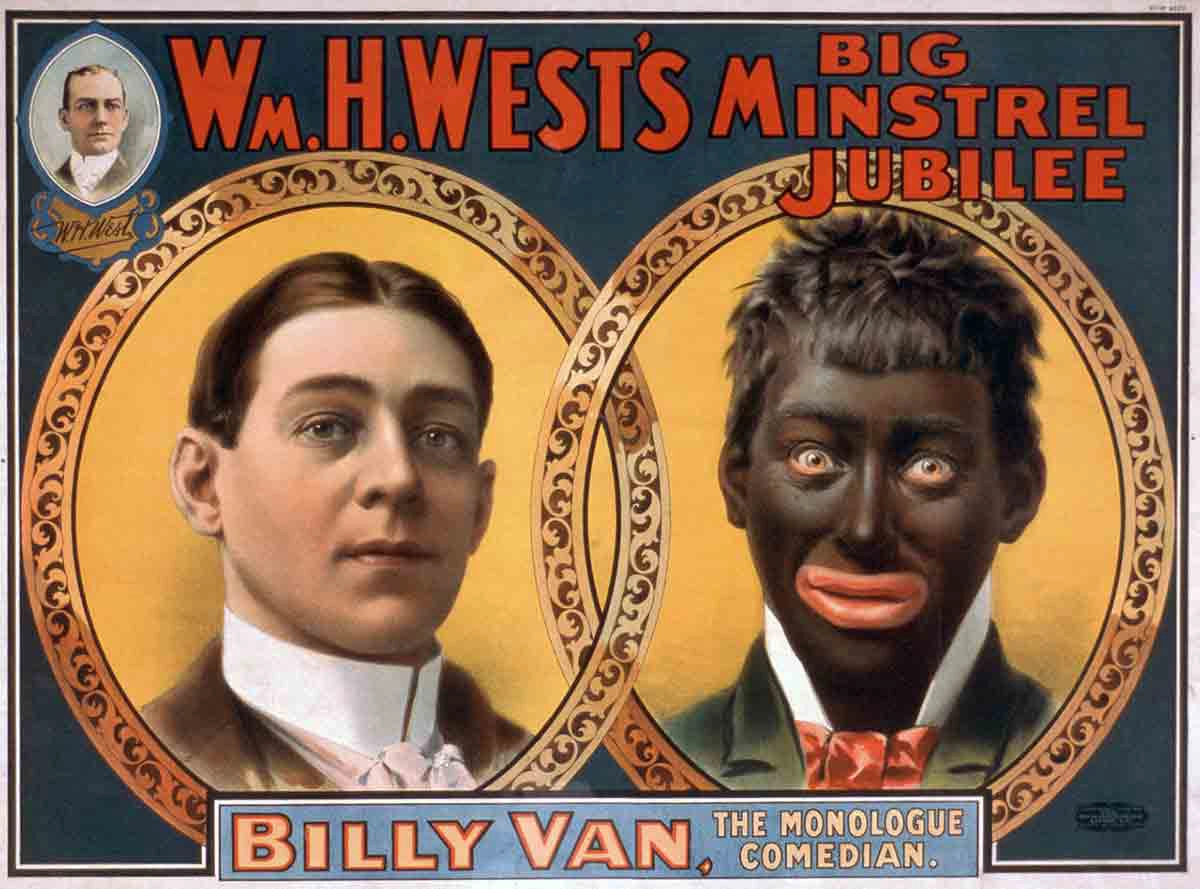

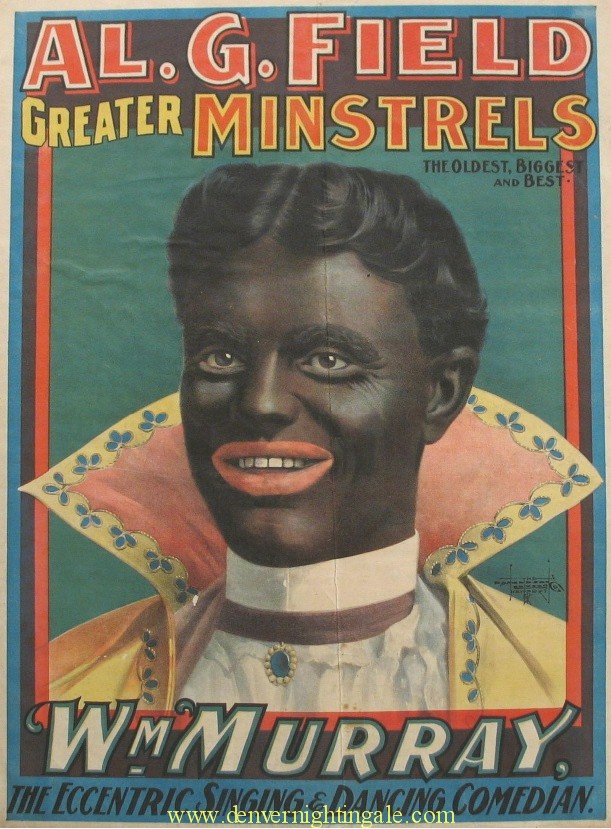

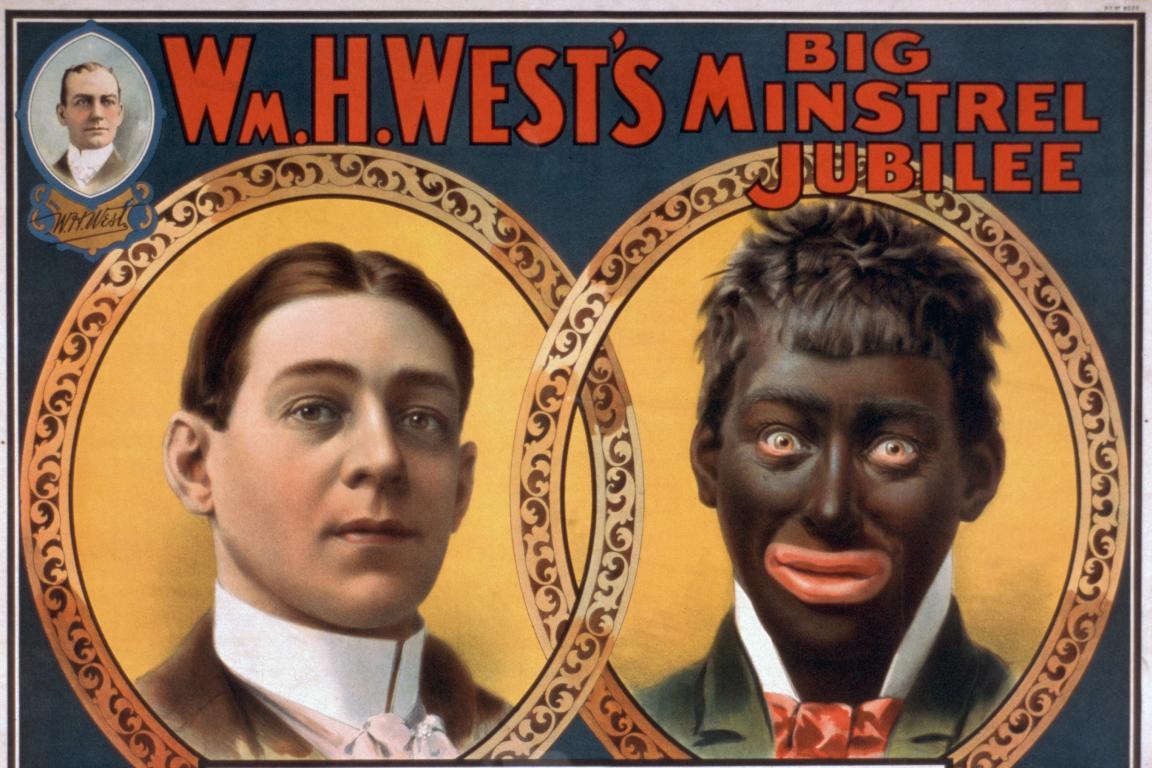

Origins and Rise of Blackface Minstrelsy

What Was Blackface Minstrelsy?

- White performers in burnt-cork makeup

- Mocked Black speech, dance, music, and mannerisms

- Became the most popular U.S. entertainment form of the 19th century

How It Began

- Thomas D. Rice performs “Jim Crow” (1820s–30s)

- Claims to imitate Black performers he observed

- Virginia Minstrels (1843) create the first full minstrel troupe

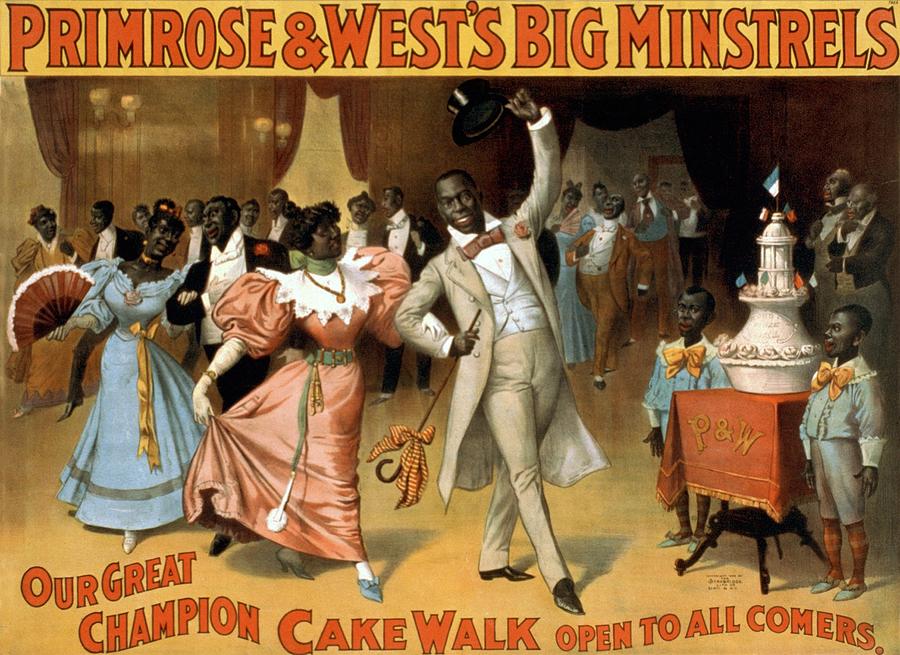

Typical Show Format

- Act I: Semicircle jokes & songs

- Olio: Variety acts, dancers, novelty pieces

- Finale: Comic skit or farce

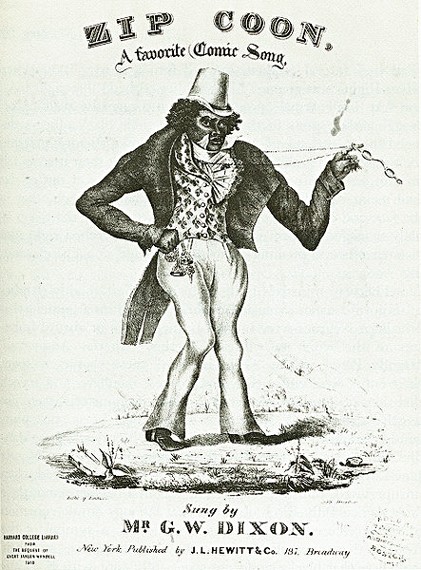

Stock Characters: “Jim Crow” (rural buffoon), “Zip Coon” (urban dandy), “Mammy”.

Historical racist imagery shown for educational analysis.

Why Minstrelsy Mattered

Cultural Function

1) United White Audiences Across Class Lines

- Working-class and elite venues

- North and South attended

- Forged a shared “American” culture through racism

2) Cultural Borrowing with Racist Caricature

- White performers adopted Black music, dance, and humor

- Simultaneously portrayed Black people as inferior, childlike, comic

- Consumed the culture while denying the humanity of its creators

3) Justified Slavery and Racial Hierarchy

- Stage myths of “happy” enslaved people

- Normalized claims of “natural” racial inferiority

- Made racism entertaining—therefore ordinary

The Central Contradiction of Minstrelsy

Simultaneous Fascination and Dehumanization

- White audiences loved Black music and dance

- But could only enjoy it through racist caricature

- Cultural borrowing combined with dehumanization

What This Reveals About American Culture

- White Americans drawn to Black expressive culture

- But unwilling to treat Black people as equals

- Pattern continues: jazz, blues, rock, hip-hop — borrowed without equal respect

Historical Significance

- First truly national mass entertainment (North + South)

- Template for American variety entertainment (→ vaudeville → Hollywood → TV)

- Shaped American racial imagination for generations

Mass entertainment and racism emerge together in the U.S.

Blackface Minstrelsy

What Is Minstrelsy?

Blackface minstrelsy: White performers in blackface makeup performing racist caricatures of Black Americans

- Emerges in the 1830s–1840s

- Becomes the most popular form of American entertainment by mid-century

- Performed across class lines—in elite theaters and working-class venues

The Minstrel Show Format

- Part 1: Plantation scenes with singing, dancing, comic exchanges

- Part 2: "Olio" or variety section with individual acts

- Part 3: One-act farce or skit

- Stock characters: Jim Crow (rural slave), Zip Coon (urban dandy)

.jpg)

The Ideology of Minstrelsy

Racist Stereotypes

Minstrelsy portrays Black Americans as:

- Childlike, ignorant, lazy

- Happy in slavery

- Incapable of citizenship or self-governance

- Comic, ridiculous, non-threatening

Political Function

Minstrelsy serves to:

- Justify slavery by depicting enslaved people as content

- Oppose abolition by mocking Black claims to freedom and equality

- Define whiteness by contrast—to be white is to be NOT Black

- Unite white working and middle classes around shared racial identity

The Paradox of Fascination

White Americans are simultaneously attracted to and repulsed by Blackness

- Desire: Black music, dance, style, and expressiveness fascinate white audiences

- Anxiety: This attraction threatens white identity and hierarchy

- Solution: Minstrelsy allows whites to "play Black" while maintaining racial boundaries

Blood Sports, Boxing,

and Working-Class Masculinity

Blood Sports as Rough Amusement

Types of Blood Sports

- Cockfighting: Roosters fitted with metal spurs fight to the death

- Dogfights: Pit bulls and terriers battle in underground rings

- Rat-baiting: Dogs kill as many rats as possible in a pit

- Bare-knuckle fights: Human boxing without gloves, few rules

Social Meaning

Working-class masculine sociability and defiance of middle-class restraint

- Held in Five Points and Bowery taverns, cellars, and back rooms

- Heavy gambling on outcomes

- Often illegal yet widely practiced

- Entrepreneurs monetize despite reformers' opposition

Sets the stage for the culture of the prize ring

Boxing and the Culture of the Prize Ring

The Sporting Fraternity

Bare-knuckle prizefighting: Illegal, staged in secret venues

"The fancy" or "sporting men"—subculture of fight enthusiasts

Who Were the Sporting Men?

Diffuse subculture around prizefighting spanning urban America

- Working-class men: butchers, mechanics, firemen, tavern keepers

- Across different ethnic backgrounds but united by sporting culture

- Found in every major city from New York to New Orleans

Shared Culture of "The Fancy"

- Sports newspapers: Spirit of the Times and similar publications

- Tavern gatherings: Discussion and planning of matches

- Insider slang: Specialized vocabulary marking membership

- "Flash" style: Distinctive dress and swagger

- Fan identity: Following fights, knowing fighters, attending matches

Prizefighting creates a working-class male counterpublic—an alternative public sphere with its own values and heroes

P. T. Barnum:

The Art of Humbug

Barnum's American Museum (1841–1865)

Overview

Established in 1841, Barnum's five-story museum attracted over 15 million visitors during its 24-year run

What Was Inside?

- Natural curiosities: Stuffed animals, geological specimens, natural oddities

- Living "human wonders": People with unusual physical characteristics

- Theatrical performances: Plays, musical acts, variety shows

- Scientific lectures: Educational talks (allegedly)

- Elaborate hoaxes: Fake mermaids, questionable artifacts

Hybrid Institution

A unique combination of:

- Moral lecture hall

- Curiosity cabinet

- Theater

- "Freak show"

Cross-Class Appeal

- Broadway location: Respectable enough for middle-class families

- Low admission (~$0.25): Affordable for working-class visitors

- Cross-gender appeal: Women and children explicitly welcomed

- Marketed as educational and moral

Humbug as an Art Form

Famous Hoaxes

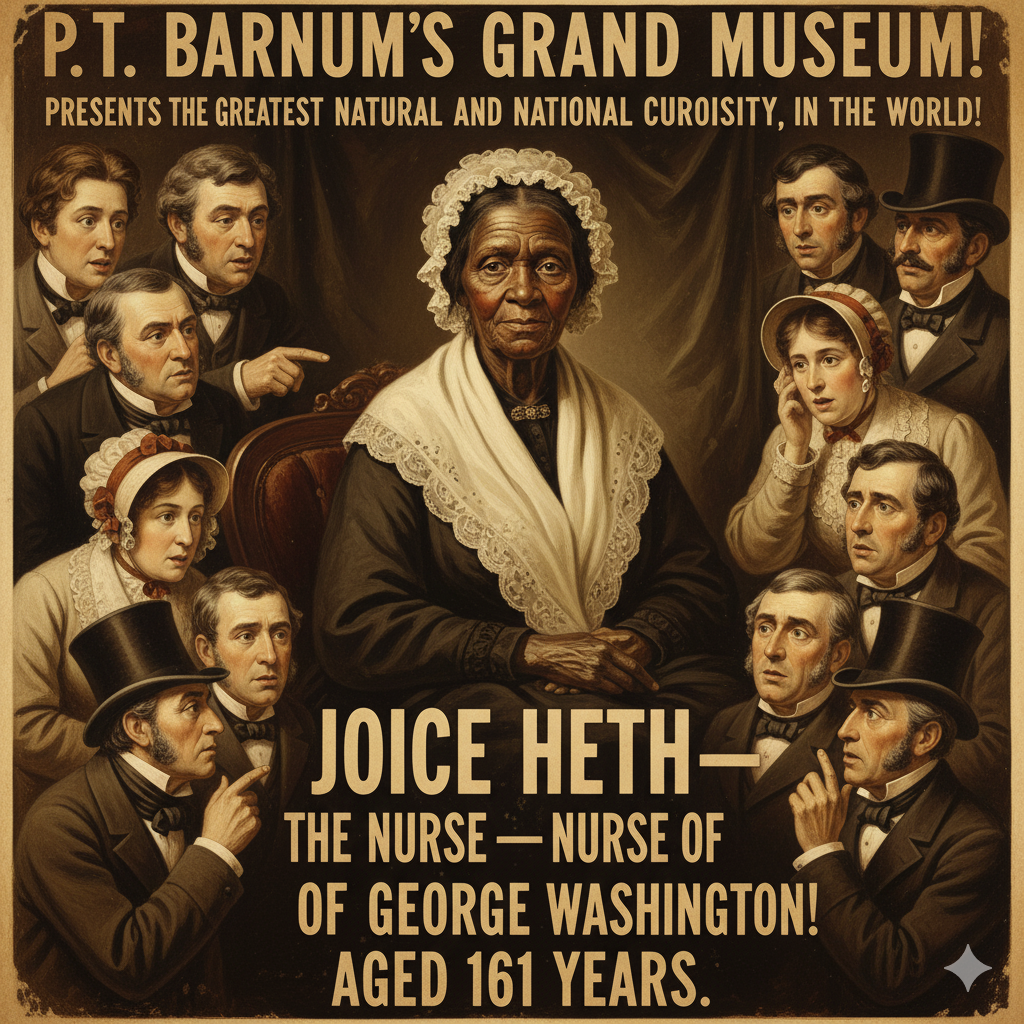

Elderly Black woman Barnum claimed was 161 years old and George Washington's former nurse. Obviously false, but thousands paid to see her.

Taxidermy creation combining a monkey torso with a fish tail. Barnum presented it as authentic with fake scientific credentials.

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

What Is Humbug?

Humbug: A blend of education, fraud, and emotional manipulation

- Not simple deception—audiences know they might be fooled

- The desire to be deceived is part of the pleasure

- Spectacle of belief and doubt performed publicly

- Value measured by experience rather than authenticity

The question isn't "Is it real?" but "Is it worth my quarter?"

Barnum's Rhetoric and Politics

Democratic Achievements

- Low prices: Makes culture accessible across class lines

- Broad access: Welcomes women, children, working class

- Participatory culture: Audiences actively debate and judge

- Meritocracy of pleasure: Your enjoyment is what matters, not your refinement

Problematic Aspects

- Exploitation: Displays people with disabilities as "freaks"

- Racial mockery: Perpetuates racist stereotypes (Joice Heth)

- Deception for profit: Capitalizes on gullibility

- Commercialization: Everything becomes commodity

Barnum represents both the promise and the problems of democratic commercial culture

He democratizes access but also exploits vulnerability. He empowers audiences but also manipulates them. He challenges elite culture but creates new hierarchies of his own.

"A little learning is a dangerous thing;

Drink deep, or taste not the Pierian spring."

The Bowery

The Bowery B'hoy

Distinctive working-class masculine identity:

- Flashy dress style (loud shirts, soap-locked hair)

- Swagger and aggressive posture

- Loyalty to fire companies and neighborhood

- Rejection of middle-class respectability

- Physical toughness and street smarts valued over education

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

Bowery Fire Companies

Social Function of Fire Companies

- Volunteer fire brigades: Essential civic service before professional fire departments

- Working-class social clubs: Centers of male sociability and identity

- Political machines: Connected to Democratic Party ward politics

- Competitive culture: Rivalries between companies, sometimes leading to fights

- Masculine performance: Physical courage, loyalty, and toughness on display

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

Five Points

Five Points: America's Most Infamous Slum

- Intersection of five streets in Lower Manhattan

- Home to Irish and Black New Yorkers in extreme poverty

- Notorious in middle-class imagination as site of vice and danger

- Actually: Complex community with families, churches, mutual aid societies

- Underground economy of entertainment and survival

Physical Mastery as Democratic Metaphor

Rather than by birth or wealth, a man's worth is demonstrated through physical courage and skill

The body becomes the site of value and citizenship—physical prowess equals democratic legitimacy

Rejection of "refinement" and self-restraint as elite values—toughness, not polish, defines the man

Democratic Ideology of the Prize Ring

In the ring, all men are equal—only strength, skill, and courage matter. Birth and wealth count for nothing. The working-class body becomes a democratic symbol.

The prize ring offers an alternative vision of American democracy—one based on physical prowess rather than property or education

Democratizing Curiosity and Emotion

Barnum's Democratic Genius

Everyone can participate in the game of belief and doubt—you don't need education or refinement

Audiences perform sophistication by debating authenticity with each other

Commercialization of wonder and feeling forms a public around shared experience

Creating "The Public"

Shared spectacular experiences produce "the public"

Strangers become a community through common experience of spectacle, debate, and collective judgment

Persistent Tension

Democratization vs. Exploitation

Does Barnum empower audiences or manipulate them? Does he democratize culture or commercialize human dignity?