Lecture 1

The Democratization of Culture:

Print, Literacy, and the New Public

Popular Culture in America, 1815–1850

Key Concepts

What is "Popular Culture"?

- Culture produced for and consumed by ordinary people (not just elites)

- Commercially produced and distributed for mass audiences

- Accessible, affordable, entertaining

- Distinguished from "high culture" — BUT boundaries are blurring

What is "Democratization of Culture"?

- Expanding cultural access beyond traditional elite gatekeepers

- Lower costs, new technologies (steam press), new institutions (lyceums)

- Culture becomes market-based rather than patronage-based

CRITICAL QUESTION: Democratization for whom?

Who gains access and who remains excluded?

Setting the Scene: 1815

A Cultural Turning Point

- Post-War of 1812 nationalism and rising literacy

- Urban growth and expanding markets

- Steam technology enables faster printing

- Cultural institutions begin to democratize

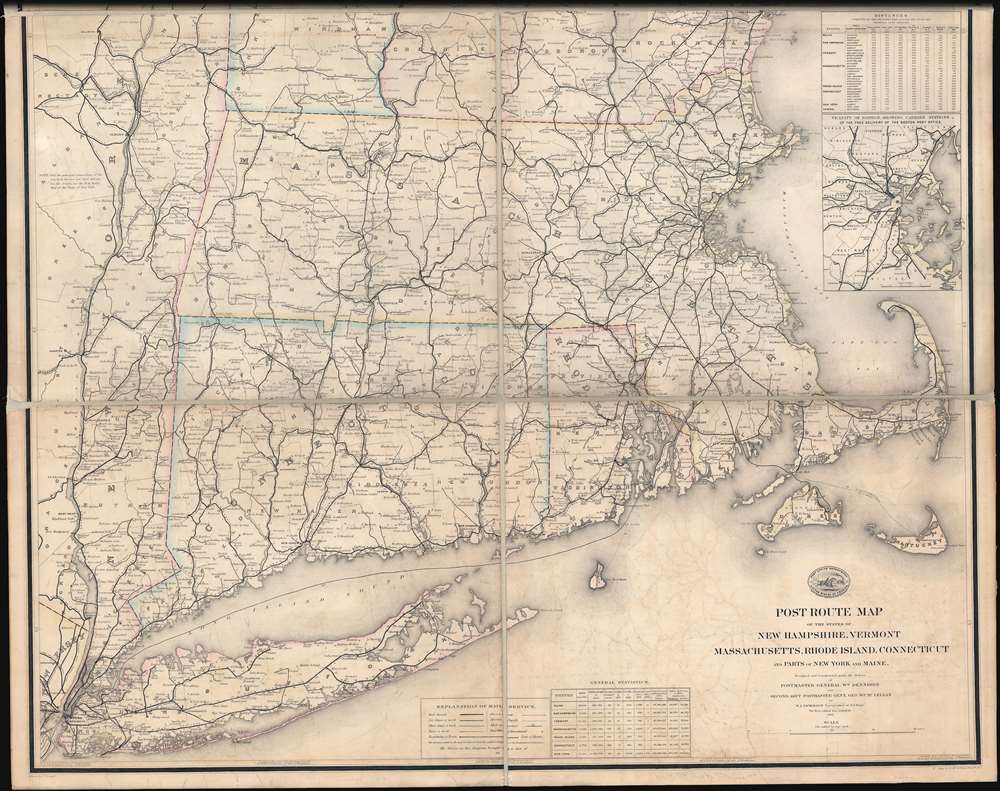

🏛️ THE POSTAL ACT OF 1792

The Information Superhighway

Newspapers mailed at extremely low rates (often free between publishers)

Creates a national information network: news from Washington reaches frontier towns

Why would the federal government subsidize newspaper distribution?

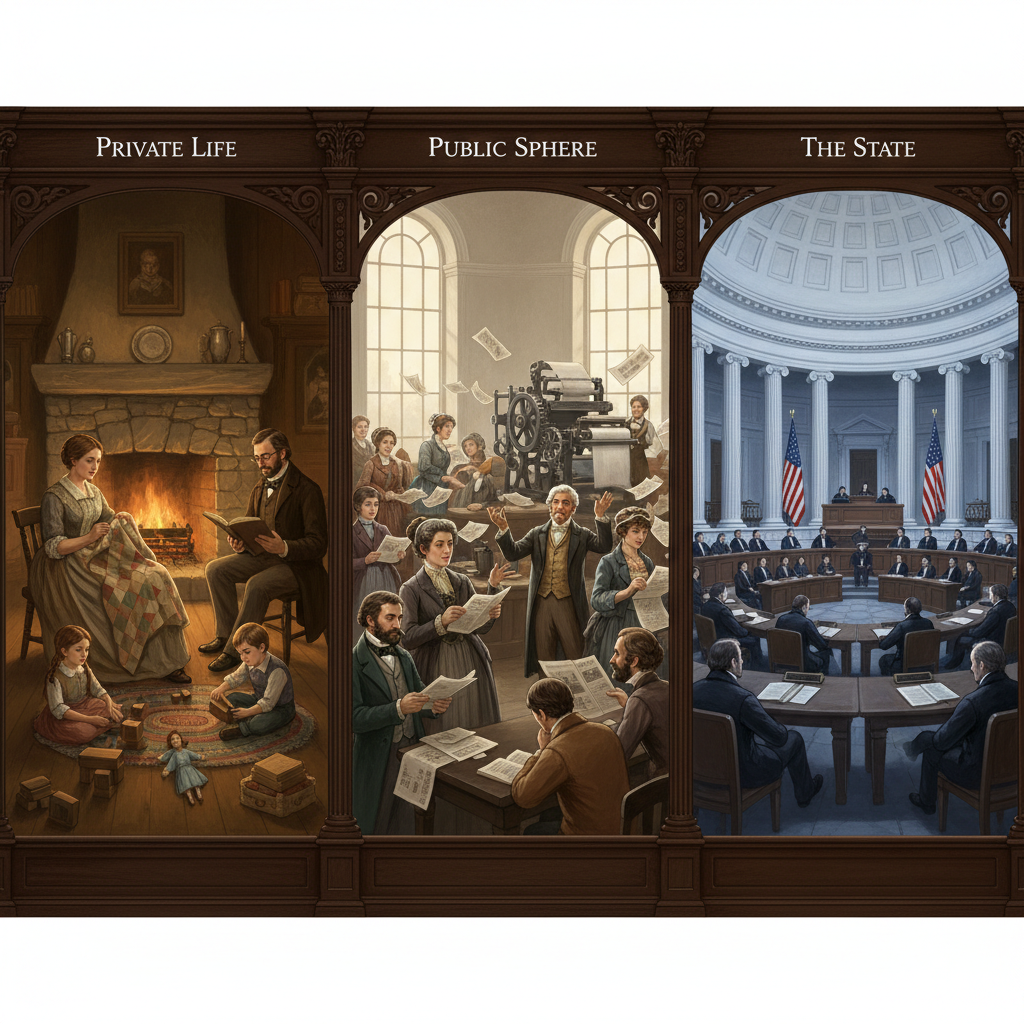

Understanding the Public Sphere

What is the Public Sphere?

- A social space where private individuals discuss public matters

- Distinct from private life (family, home)

- Distinct from the state (government)

- Created through communication—newspapers, pamphlets, lectures

- Access based on literacy and participation (ideally)

How Print Creates the Public Sphere

The Power of Print

- Newspapers circulate information to geographically dispersed readers

- Readers imagine themselves as part of a larger community of "the public"

- Print enables debate, discussion, and formation of public opinion

- Penny press makes participation affordable (1¢ vs 6¢)

- Lyceums bring public lectures to ordinary citizens

CONCRETE EXAMPLE:

A farmer in Ohio and a merchant in Boston both read about the same Senate debate in their local newspapers. Though they've never met, they now share knowledge and can discuss the same political issue. This is the public sphere in action.

The Public Sphere: Who's Excluded?

Key Question: Who has access to this "public" sphere?

- ✓ White men (primary participants—voting rights, literacy, leisure time)

- ◐ Some middle-class women (limited roles—reading circles, moral reform societies)

- ✗ African Americans (largely excluded, create separate spheres—Freedom's Journal, 1827)

- ✗ Enslaved people (legally barred from literacy in most Southern states)

- ✗ Working poor (economic barriers—time, cost, limited literacy)

"Democratization" is partial and contested—access remains structured by race, class, and gender.

The Print Revolution: Scale & Impact

Technological Innovation

- Steam presses, mass-produced paper, stereotyping

Economic Innovation

- Advertising replaces subscriptions as primary revenue

Social Impact

- Literacy expands across class and region

- Print becomes a commodity, not a luxury

Key Example

- Benjamin Day's New York Sun (1833)—news for a penny

BY THE NUMBERS

- ~1,000 newspapers by 1835

(vs. ~200 in 1800) - ~75% literacy among white men

- ~50% among white women by 1840

- Book prices drop from $1.50 to 25¢

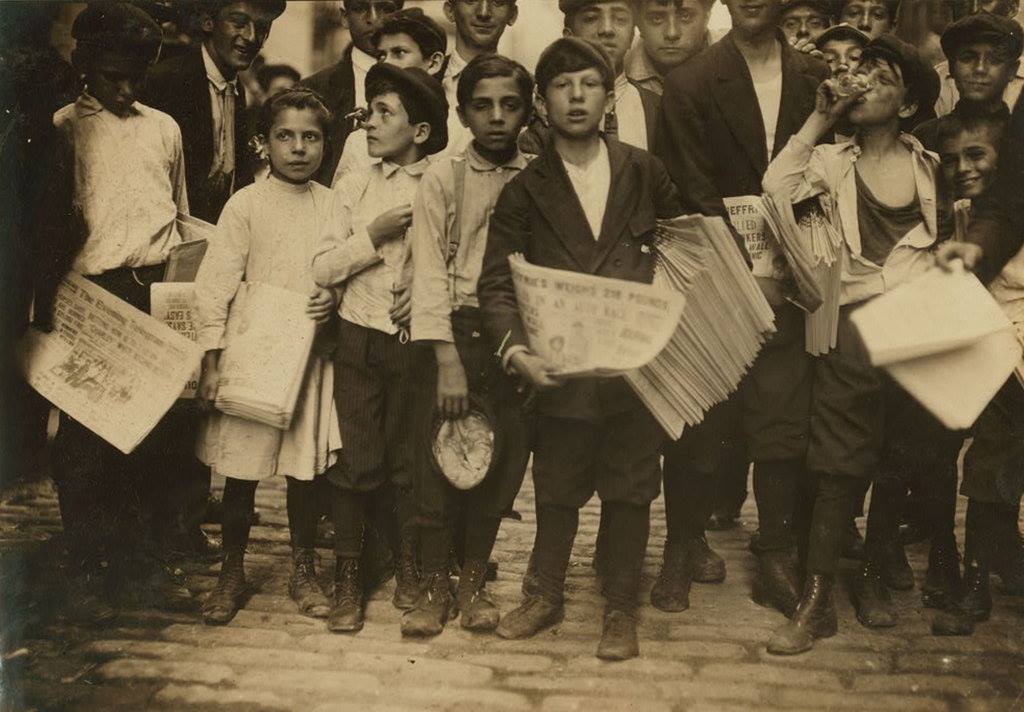

The Penny Press: A New Business Model

The Innovation

- Newspapers sold for 1¢ (not 6¢)—affordable to working-class readers

- Sold on streets by newsboys, not by subscription

- Advertising revenue replaces subscriber fees

- Mass circulation = mass influence

The Players

- New York Sun (1833) – Benjamin Day

- New York Herald (1835) – James Gordon Bennett

- New York Tribune (1841) – Horace Greeley

Why would selling papers on the street change what gets published?

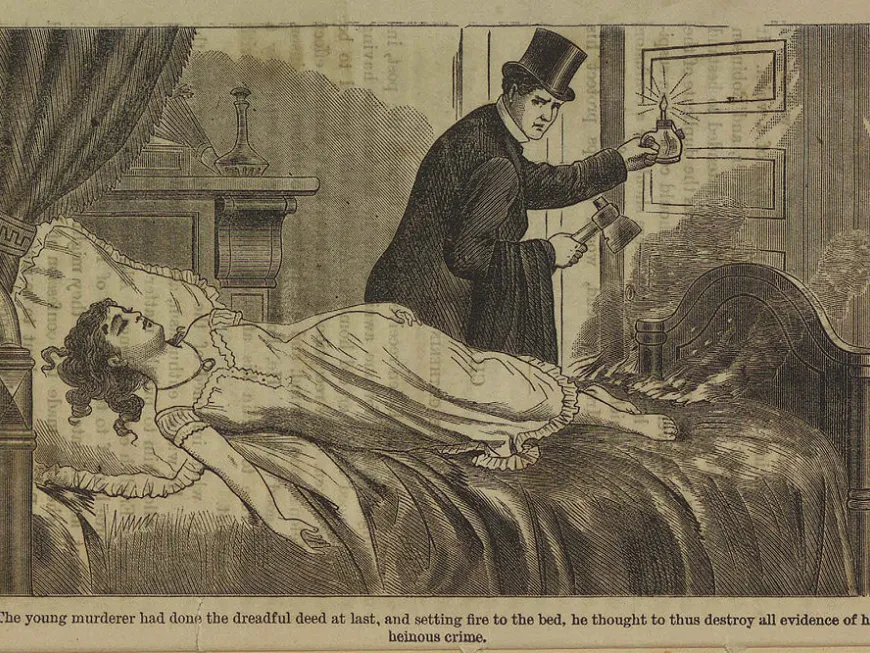

Sensationalism: Where's the Line?

What the Penny Press Published

- The Great Moon Hoax (1835): “scientists” discover winged humanoids on the moon

- Helen Jewett murder case (1836): sex worker’s death becomes daily drama

- Crime, scandal, spectacle — anything that sells papers

CRITICAL QUESTION:

Where is the boundary between truth and entertainment?

Impact on Democracy

- Ordinary readers become participants in shared public conversation

- Journalism shifts from “information” to “performance”

The Book Revolution

Publishing Explosion

- Harper & Brothers, Carey & Lea pioneer cheap editions

- James Fenimore Cooper’s Leatherstocking Tales create frontier mythology

- Serialization in story papers creates new reading habits

- Books become affordable commodities, not luxury items

IMPACT:

Reading becomes a form of leisure, self-improvement, and identity formation. Americans begin to imagine themselves through the stories they read—whether tales of frontier adventure or sentimental domestic life.

Sentimental Fiction & Female Readers

The "Scribbling Women"

- Susan Warner (The Wide, Wide World, 1850)

- Maria Cummins (The Lamplighter, 1854)

- E.D.E.N. Southworth (The Hidden Hand, serialized)

Cultural Significance

- Blend of sentiment and moral didacticism

- Novels teach "emotional literacy"—feeling becomes virtuous

- Female reading publics gain cultural authority

Link forward: Emotional reading prepares ground for Lecture 2's religious feeling

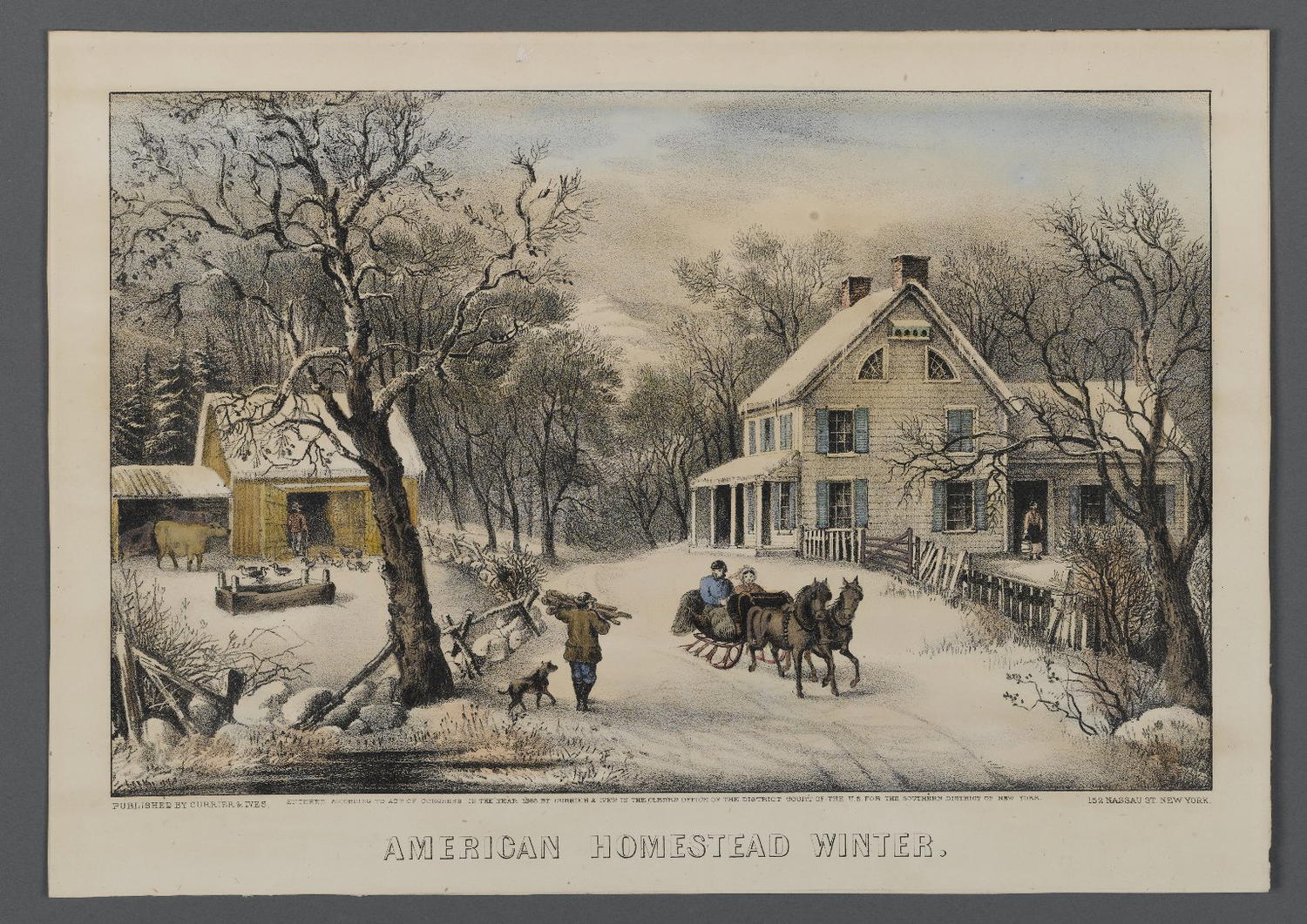

Visual Print Culture: Images for the Masses

Lithography Revolution (1820s–1830s)

- Cheap decorative prints enter middle-class homes

- Currier & Ives (founded 1834) mass-produce American scenes

Political Cartoons & Illustrated Newspapers

- Visual culture democratizes alongside textual culture

- Images shape national myths — frontier, domesticity, prosperity

Americans could now see idealized versions of themselves and their nation hanging on their walls.

The Lyceum Movement: Education, Culture, and Spectacle

What Were Lyceums?

The Lyceum movement began in the 1820s as a network of local associations devoted to adult education, civic improvement, and moral uplift. These organizations hosted lectures, debates, and demonstrations designed to bring knowledge to ordinary citizens.

Founded by Josiah Holbrook in 1826, the lyceum became the backbone of antebellum public culture—where Americans could learn about science, literature, reform, and philosophy outside formal schools.

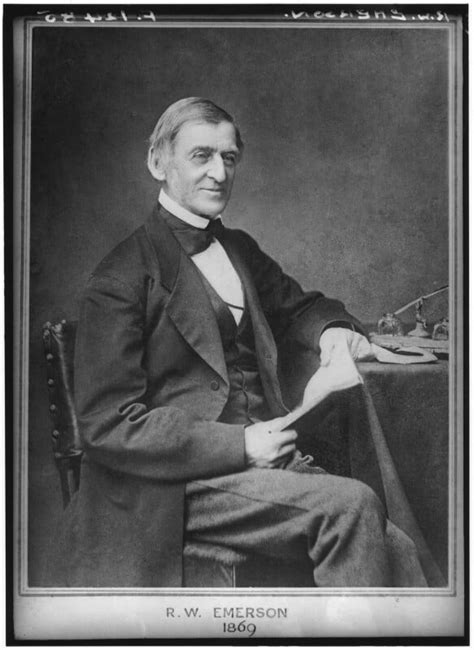

High Culture and Moral Philosophy

Prominent writers and thinkers like Ralph Waldo Emerson brought Transcendentalist ideas to Lyceum audiences. Their lectures on self-reliance, moral philosophy, and the pursuit of truth helped popularize intellectual and literary culture among the middle class.

Emerson’s tours through small towns and city halls made philosophy a public performance, accessible to tradesmen, teachers, and farmers alike.

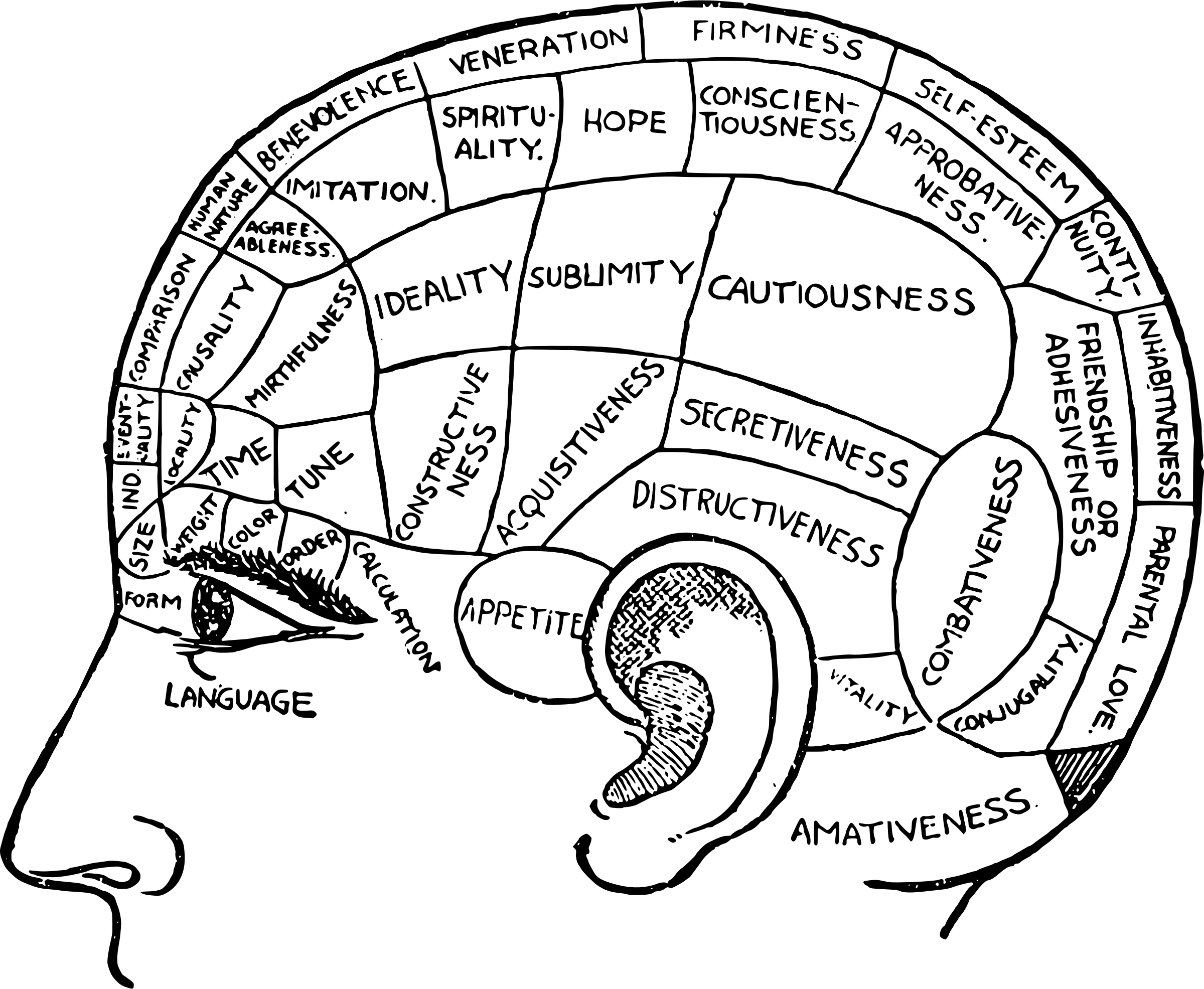

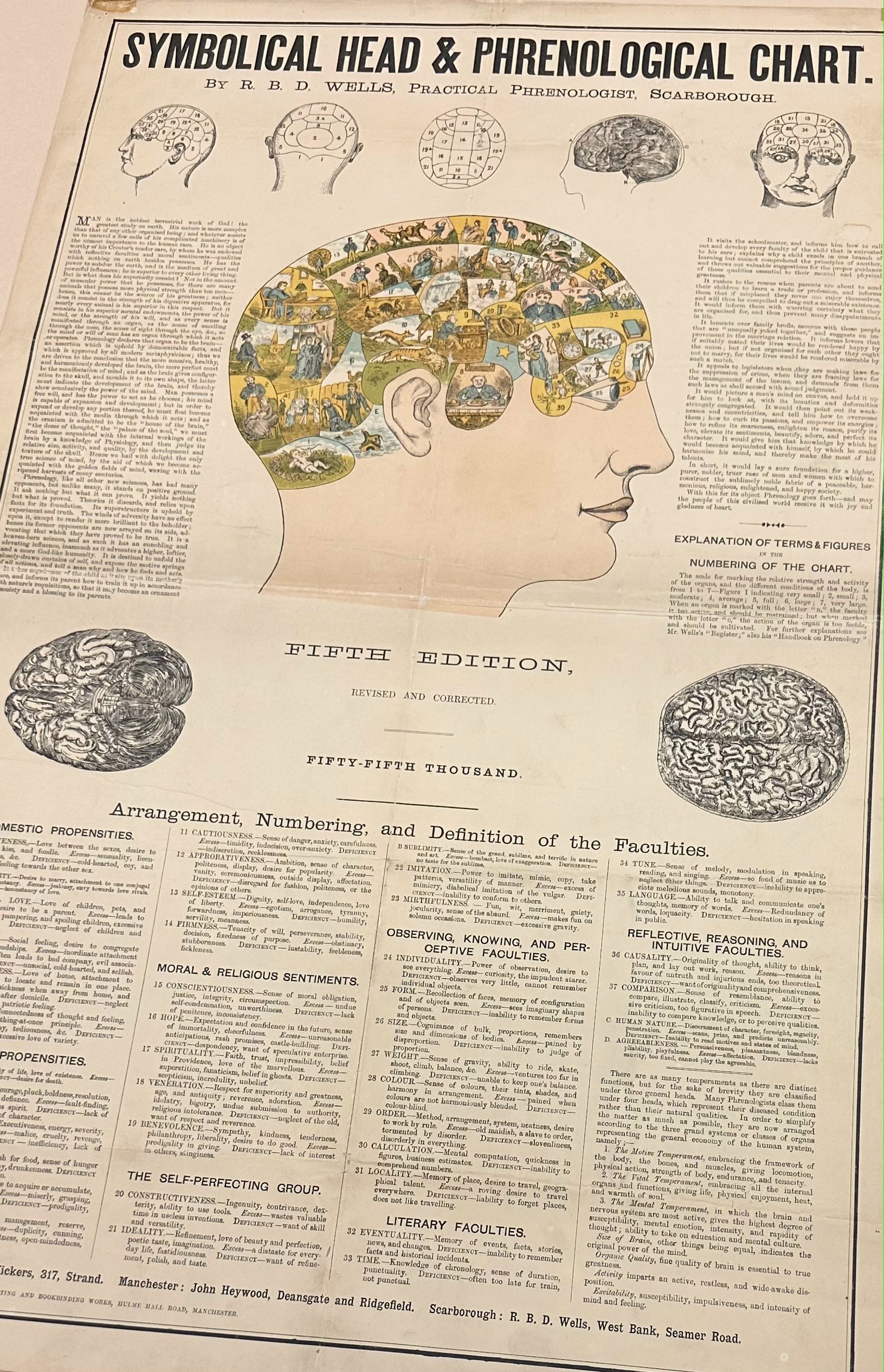

Popular Science and Spectacle

Alongside high-minded philosophy, Lyceum stages also hosted demonstrations of phrenology, mesmerism, and electrical experiments—blurring the line between education and entertainment.

Figures like Orson and Lorenzo Fowler delivered engaging phrenology lectures, promising moral and personal insight through the “science” of skull reading. These popular pseudo-sciences reflected Americans’ hunger for self-knowledge and moral order.

Critical Question:

Was the Lyceum a democratic classroom or a performance stage? Did it elevate the public or merely entertain them?

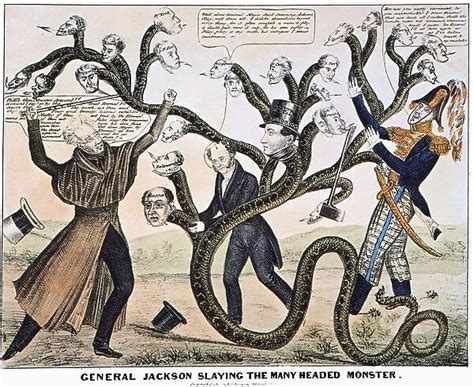

Print and Politics: From Pamphlet to Partisan Press

Political Mobilization Through Print

- Broadsides and party newspapers link print to mobilization

- Jacksonian era's "partisan press" turns voting into spectacle

- Editorials and cartoons appeal to working-class readers

- Political participation becomes a form of popular entertainment

KEY CONCEPT: Print makes politics accessible and exciting—but also partisan and emotional

Conclusion: Print and the Making of American Culture

Main Argument:

Print didn't just spread information—it created a new kind of public and a new kind of American identity. But democratization had limits: access remained structured by race, class, and gender.

Next Time: Lecture 2

From print culture to spiritual culture—camp meetings, revivals, and the democratization of religion. Who gets to define American faith?