The Myth of the Lost Cause

Part 2: Institutionalization & Growth

How the Lost Cause Became Embedded in American Society (1880s-1920s)

HIST 102: U.S. History Since 1877

⌨️ Keyboard Shortcuts

| → / ← | Next / Previous slide |

| F | Fullscreen mode |

| S | Speaker notes view |

| O / Esc | Overview mode |

| B / . | Blackout screen |

| ? | Show all shortcuts |

Tip: Press S on a second monitor for presenter view with notes.

Introduction

From Regional Coping to National Memory

The transformation of the Lost Cause after 1877

Where We Left Off

In Part 1, we traced how the Lost Cause emerged:

- First as a wartime coping mechanism

- Then as a postwar apologetic project

We examined its core claims:

- The war wasn't about slavery

- Enslaved people were loyal and content

- Confederate leaders were saints

- Southern society was harmonious and superior

- Fanatical abolitionists caused the war

Today: how these claims became a national memory regime.

Understanding the Lost Cause as a Memory Regime

The Lost Cause isn't merely wrong.

It is a Memory Regime

- Intentionally constructed

- Deliberately institutionalized

- Carefully ritualized

- Fiercely defended

Memory Regime

Definition: A system of organized, institutionalized memory that shapes how a society understands its past.

- Constructed: Deliberately created by specific actors with specific goals

- Institutionalized: Embedded in organizations, schools, laws, and public spaces

- Ritualized: Maintained through regular ceremonies, commemorations, and practices

- Defended: Protected against challenges through social pressure, political power, or violence

Part I

Organizational Infrastructure

How veterans and women built the institutional muscle

United Confederate Veterans (UCV)

Founded 1889 | Peak membership: 160,000+

Structure

- Local camps organized into state divisions under national organization

- Annual reunions drew between 10,000 and 80,000 attendees

- Confederate Veteran magazine reached circulation of 20,000

Functions

- Established ritual authority for Confederate commemorations

- Vetted and approved history textbooks

- Presided over monument dedications

- Organized and sanctioned public commemorations

UCV reunion, demonstrating the scale and organization of Confederate veteran gatherings

Ritual Authority

The UCV wielded enormous symbolic power through public ceremony:

- Monument dedications: Veterans unveiled statues, giving them "eyewitness" legitimacy

- Memorial Days: Controlled the narrative at Confederate grave decorations

- Reunions: Massive public spectacles (New Orleans 1903: 80,000 attendees)

- Uniform appearances: Visual reminder of Confederate service

These rituals transformed Lost Cause claims into performed truth. Hard to argue with men who "were there."

Textbook Vetting

The UCV created Historical Committees to approve or condemn school textbooks:

- Process: Committees reviewed textbooks for "fairness to the South"

- Criteria: Books must not call Confederates "traitors" or emphasize slavery as the war's cause

- Enforcement: Condemned books faced boycotts; approved books gained veteran endorsement

- Impact: Publishers self-censored to access Southern markets

Veterans used moral authority ("we fought the war") to control how the next generation learned about it.

United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC)

Founded 1894 | Peak membership: 100,000+ (by 1920s)

UDC monument dedication ceremony

While men had veteran status, women did the work. The UDC was the institutional engine that transformed Lost Cause memory from talk into monuments, textbooks, and ritual.

UDC Activities

Monument Work

- Raised funds (bake sales, bazaars, donations)

- Commissioned sculptors

- Selected courthouse square locations

- Organized dedication ceremonies

Result: Over 700 Confederate monuments by 1930s

Educational Campaigns

- Lobbied school boards for "correct" textbooks

- Sponsored essay contests on Confederate heroes

- Donated books to school libraries

- Created "Children of the Confederacy" youth chapters

Goal: Generational transmission of Lost Cause memory

Part II

Landscape & Education

Making Lost Cause memory physically and pedagogically inevitable

The Monument Campaign

Monument unveiling ceremony, early 20th century

Confederate monuments peaked in two waves:

These monuments weren't erected immediately after the war when Southerners were mourning. They were built decades later, during Jim Crow—when white supremacy needed public reinforcement.

Monument Dedications as Ritual

Veterans and schoolchildren at monument dedication

Dedications weren't quiet ceremonies. They were massive public spectacles:

- Parades of veterans in uniform

- School children in Confederate-themed pageants

- Speeches by governors, senators, veterans

- Crowds of 5,000–20,000+ in small Southern towns

The dedication ritual mattered as much as the monument itself—transforming Lost Cause claims into performed civic religion.

The Textbook Wars

Control the textbooks, control the future.

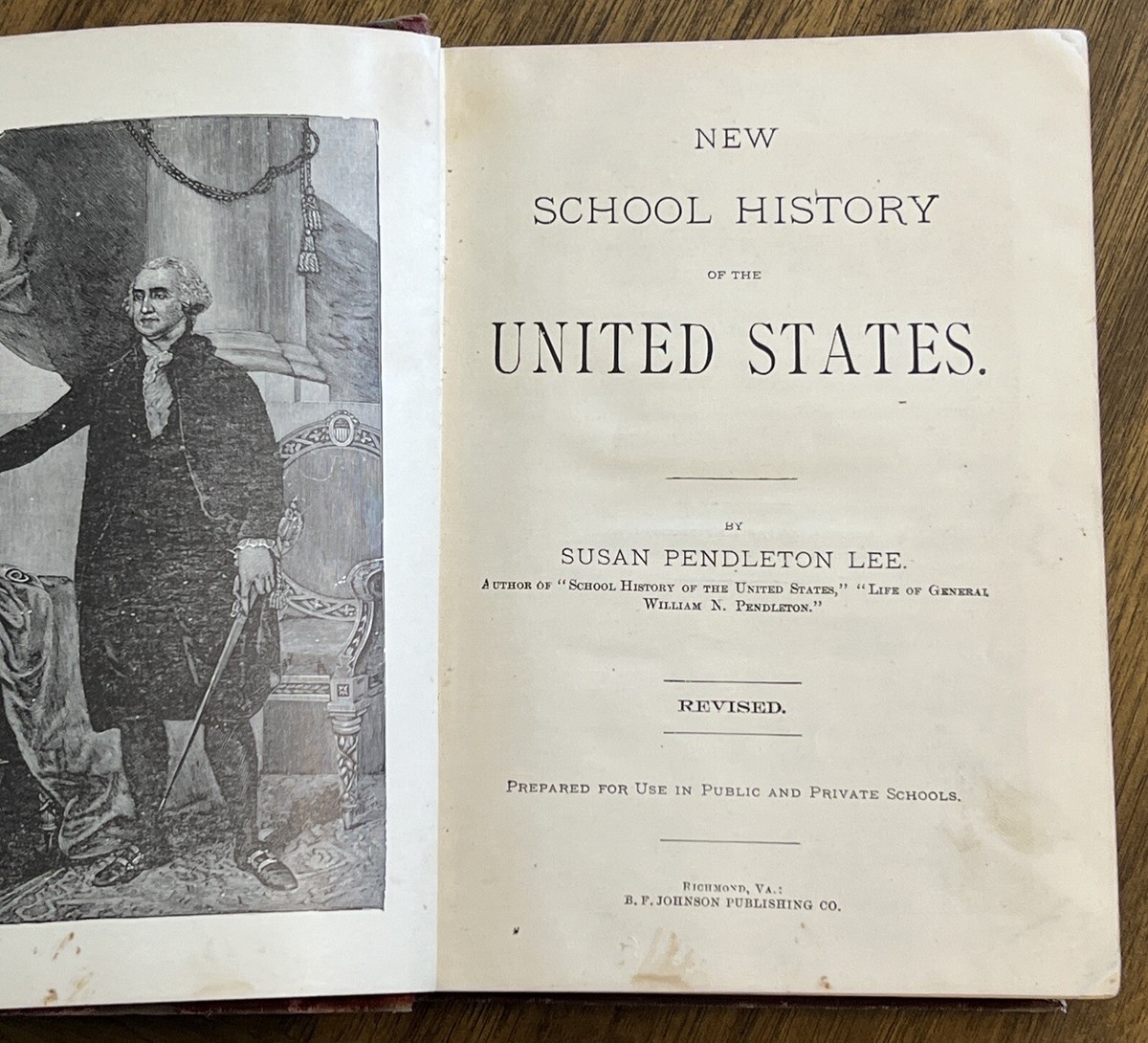

Lee's School History (1895)

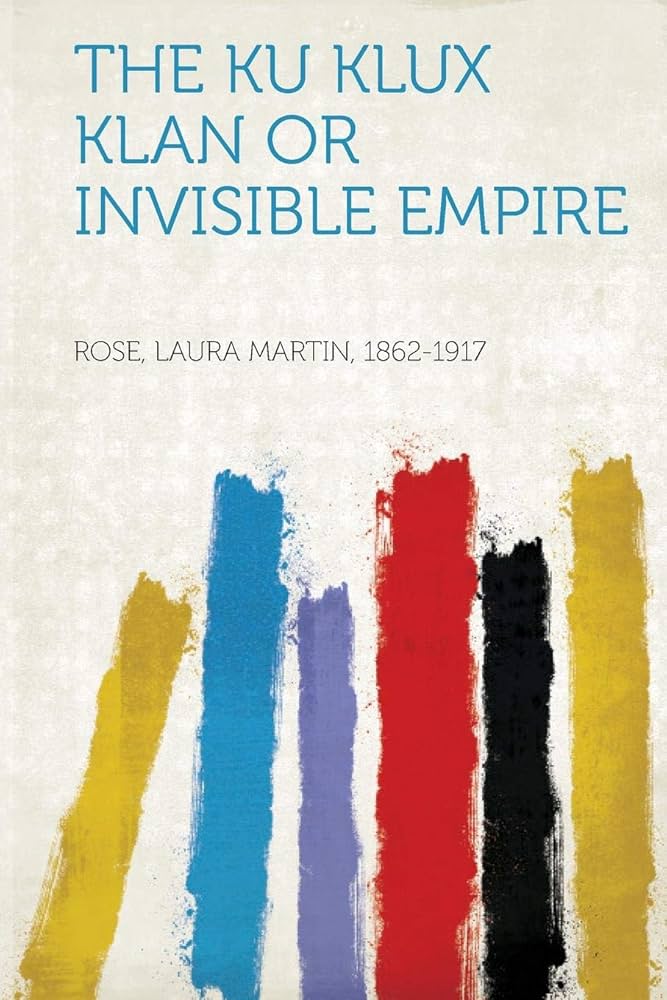

Rose's Invisible Empire (1914)

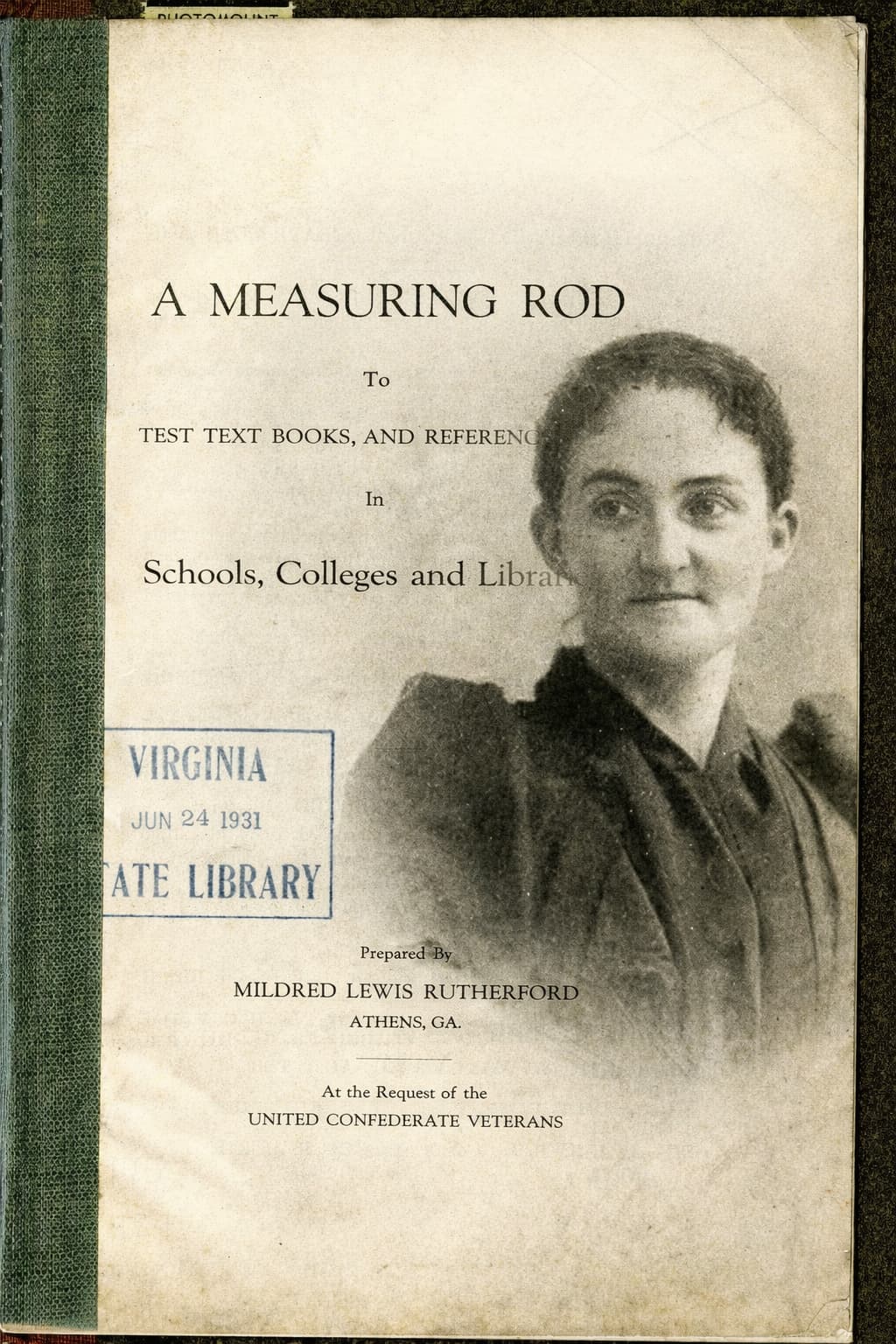

Mildred Rutherford: Historian General of the UDC

Rutherford's Measuring Rod (1919)

Title: "Historian General" (1911-1916)

Mission: Ensure "truthful history" taught in Southern schools

Strategy:

- Created A Measuring Rod to Test Text Books

- Lobbied state legislatures

- Organized textbook boycotts

- Pressured publishers directly

Impact: By 1920s, most Southern states required "fair" treatment of Confederacy in textbooks

A Measuring Rod to Test Text Books (1919)

Purpose: Provide UDC chapters with specific criteria to evaluate school textbooks

REJECT a book that:

- Calls the Confederate movement a "rebellion"

- Says the South fought to preserve slavery

- Speaks of the Constitution "as practically obsolete"

- Admits that the North was right in its course

ACCEPT a book that:

- Refers to "The War Between the States" (not "Civil War")

- Emphasizes states' rights and constitutional issues

- Portrays enslaved people as loyal and content

- Describes Reconstruction as a disaster

This was institutional censorship disguised as quality control.

Part III

National Reconciliation

How the North became complicit in Lost Cause mythology

Blue-Gray Reunions

By the 1880s-1910s, Union and Confederate veterans began holding joint reunions.

"Both sides fought bravely for what they believed. Let's honor all veterans and heal the sectional wound."

What this narrative erased:

- Slavery as the war's cause

- Emancipation as the war's meaning

- Black veterans and their sacrifices

- The moral difference between fighting for union/freedom vs. fighting for slavery

The Spanish–American War (1898)

A war that helped the nation “re-unite”—not by resolving Civil War conflicts, but by redirecting attention outward.

What United Them

- Common external enemy (Spain) redirected energy away from sectional conflict

- Shared military service (including ex-Confederates) helped restore Southern honor and national unity

- Parades, medals, and hero stories turned reunion into popular culture

- The war fueled the Reconciliation narrative: “once divided, now Americans together”

- Imperial ambition + racialized “civilizing” views of Cubans and Filipinos

Post-1898 reconciliation worked because many white Northerners increasingly accepted:

- Southern white control of the South (Jim Crow segregation and disfranchisement)

- A national identity centered on white solidarity, often at the expense of Black Americans

What We've Covered Today

The Lost Cause didn't just happen—it was built:

Organizations: UCV and UDC provided institutional muscle

Monuments: Claimed public landscape for Confederate memory

Textbooks: Captured educational systems for generational transmission

Reconciliation: Northern complicity enabled Southern victory in memory war

Next time: How Lost Cause mythology became American culture through academia, film, and aesthetics.